Most of us pay little thought to our fork offset. Buried deep in the geometry table, it’s easily overlooked by riders and even manufacturers. Yet, as we've been been finding out, it can have a dramatic and surprising effect on a bike’s handling.

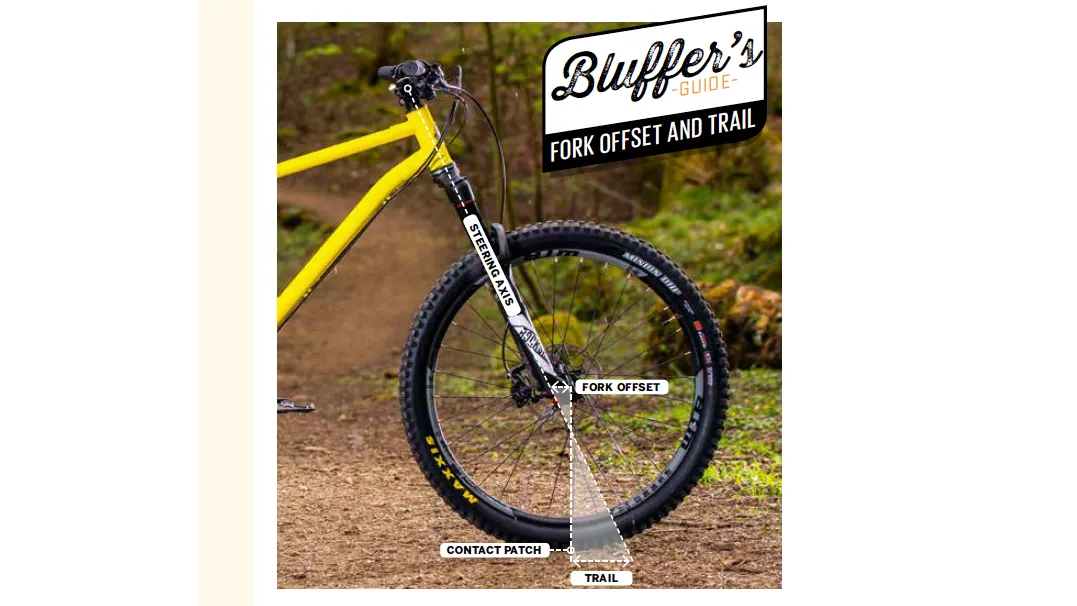

Given its relative obscurity, you might be wondering what fork offset is. Simply put, fork offset, or fork rake, is the distance between the front axle and the steering axis – the imaginary line running straight through the midpoint of the steerer tube. Fork offset is linked to another important measurement: trail.

What is ‘trail’, you ask? Trail is the horizontal distance between the steering axis and the contact patch of the front tyre. Higher trail means greater stability and lazier, slower steering. Shorter offset or a slacker head angle results in more trail (slower steering); longer offset or a steeper head angle reduces trail, quickening the steering response. Finally, into the mix comes wheel size. Bigger wheels imply more trail, as the axle is higher and so the gap between the steering axis and contact patch increases proportionally. However, 29ers use steeper head angles and increased offset to compensate for this.

Fox uses 40mm offset for 26in forks, 44mm for 27.5in and 51mm for 29in. RockShox uses similar offsets, but offers the 29in Pike in 46mm offset, as well as 51mm. In the case of my Specialized Enduro 29, the 67.5-degree head angle and 51mm offset results in a trail figure of 105mm. For comparison, let’s look at the 650b version of the Enduro – a contrast often made to establish the differences between wheel sizes.

The three fork crowns used in our experiment – giving 51mm, 44mm an 37mm offset respectively

The 650b bike is two degrees slacker at 65.5-degree and uses 42mm offset. The result is a trail figure of 120mm - 15mm more than the 29er. In other words, Specialized has over-compensated for the bigger hoops, giving a shorter trail and consequently twitchier ride on the 29in bike, in spite of the inherently more stable wheels.

A quick calculation on the back of an envelope revealed that the 29er would require a 65.7-degree head angle to achieve the same trail as its 650b brother using a 51mm offset, or 66.7-degree head angle if it shared the same 42mm offset. With the 67.5-degree head angle, the 29er would require a 36mm offset to achieve the same trail as the 650B bike.

The story is repeated by other manufacturers, who are sticking to 51mm offset and refusing to go below 67-degree head angles. This means short trail figures, which limits the aggressive-descending capabilities of big-wheeled bikes.

The experiment

Despite all this, I’m a big fan of 29ers, and my XL Specialized Enduro in particular, but it suffers from a twitchy front-end, wanting to tuck-under in really tight steep corners. Unable to slacken or lengthen the bike, the only way to remedy this is by shortening offset. I went to Mojo, Fox suspension’s UK distributor and service centre, and asked if this could be done. To my surprise, they said yes.

Related: Specialized Enduro Elite 29 review

My plan was this: to do a run of Mojo’s formidable three-minute test track with the standard 51mm offset fork, swap to a different crown giving a radical 37mm offset, repeating the track, before swapping again to a half-way-house, 44mm figure and testing a final time.

It was 8am on a very Welsh morning when I arrived at the test track. After completing a sighting run, I went to meet Mojo’s main man, Chris Porter. Over a coffee, he pointed out that to change offset would involving taking apart the fork and reassembling it with a different crown. As I had been using my 36 fork tirelessly for six months, Chris claimed this in itself would have a dramatic effect on the fork’s performance, as the fresh oil and seals would improve sensitivity.

Mojo's Chris Porter expertly refreshes Seb's fork, ready to take on the demanding test track with maximum suppleness

He was right, of course. After Chris had serviced the fork without changing the crown, we headed up for another run with the standard 51mm offset. The difference in the fork’s sensitivity was noticeable, and this second run gave me a chance to really get the feel for the track with a freshly serviced fork sporting standard offset.

We repeated one corner in particular a dozen times for the benefit of our photographer, Andy. Chris observed that I was wrestling with the bar mid-corner, readjusting my steering. After completing the run, and taking time to repeat key trail features, we headed back to Mojo HQ where Chris set about replacing the crown to give me a 37mm offset.

This made a big difference.

On the fast, straight section at the top of the hill, the bike simply felt shorter. I wouldn’t say slower, but the fact that my front axle was 14mm closer was unnervingly apparent at high speeds. Dropping into twisty woods, however, told a different story altogether. The string of rooty, tight corners which make up the test track could be carved through in smooth, calm arcs. Stopping to repeat the corner that had me fighting the bar earlier, the steering could be said to be too lazy, causing me to exit the corner slightly wide on first attempt.

Thereafter, the bike was able to tackle the berm (which follows a steep, rooty chute) with relaxed and confident handling, requiring none of the mid-corner adjustments and twitching I had experienced before. After a full run with plenty of repeated sections, I felt I had the feeling of the new geometry. It was time to get the stopwatch out.

Shorter offset allowed Seb to carve through demanding corners like this one smoothly, in a continuous flowing arc

I completed a solid run of the track, not pushing too hard. No need for heroics here, just a smooth, repeatable run was called for. The bike felt calm and controlled, never twitching or threatening to tuck-under, as it had been in the tightest bends with standard offset. The time was 3.19.2. Not my fastest time on this course, not by a long way, but conditions were slippery and I had a solid run to compare against.

After yet another F1-style pit stop at Mojo, it was back up the hill with a medium offset of 44mm – the same as a standard 650b fork from Fox. As you might expect, the handling was somewhere in-between the standard and super-short offsets used previously - not as calm and lazy as the 37mm, not as twitchy as the 51mm. After another trial run to get a feel for the 44mm offset fork, the stopwatch was applied once more.

This run felt spot-on. After getting even more acquainted with the track, I was able to hit all my braking points accurately, ride the corners on-line and felt like I was carrying good speed the whole way down. I expected to be considerably faster on this run than last, but the stopwatch told a different story. The time was 3.20.8 – 1.6 seconds slower than with the 37mm offset. Now, I’m not claiming that that time difference is significant. I’m not a good enough rider, and I’m not familiar enough with the track to get that kind of consistency (let’s go with that second reason), but the strange thing was that I felt much faster the second time round. I even checked that my brakes weren’t rubbing. Considering how much faster I felt on the second attempt, I was more than a little surprised by this result. Chris, however, was not surprised at all.

Mojo's Welsh test track fetatures dozens of corners of all shapes and sizes – it's perfect for testing a bike's handling

Chris Porter has experimented with a huge range of fork offsets on his bikes, and he has found that shorter offsets give a calmer handling bike, which tends to go faster when the stopwatch is brought to bear. Following this, Chris has landed on a 30mm offset for his own bike.

Conclusion

While it’s impossible to draw a firm conclusion from just two timed runs, it does seem that there is a very strong case for manufacturers to experiment with shorter fork offsets. It gives some of the benefits of a slacker head angle (increased trail, and therefore greater stability) while shortening the wheelbase, rather than lengthening it. In reality, it’s more complex than that, though.

Shorter offset also reduces the ‘floppy’ feeling that can occur when tackling tight corners, where the wheel can feel like it wants to tuck under. This, Chris reckons, is nothing to do with trail, but simply the fact that a longer offset will put the contact patch further inside of the bike when cornering, causing it to pull to the inside of the turn. It certainly feels this way when returning to the longer offset, as the front wheel seems to want to turn sharply on its own accord, giving a twitchy feeling. Once I got used to it, the only disadvantage I found to the shortest offset was the fact that it made my bike feel too short in the front-centre; the front axle simply was too close to the bottom bracket. Now, if the bike was longer, compensating for the short offset, that could be the recipe for a very fast bike indeed!

A note on Chris Porter’s bike

Following years of experimentation and trial by stopwatch, Chris has arrived at a truly radical geometry configuration. With a head angle as slack as 59 degrees (although usually a slightly more conventional 61), and an offset of just 30mm, Chris has a monstrous trail figure. With numbers like these, you could almost call it ridiculous.

Chris and Seb discuss the pros and cons of subtle geometry changes

Until you see him ride it, that is. When a man twice your age (sorry Chris!) is hauling down treacherous descents at a blinding pace, the time for ridicule is over. Chris believes that the extra unsprung mass of 29in wheels negates the smooth-rolling advantages of the bigger hoops, so he has stuck with 27.5in. I asked him why he didn’t use 26in wheels; he answered “you can’t get the tyres these days”.

A note on Seb Stott’s bike

As mentioned above, I'm a big fan of 29ers. After applying the stopwatch to several big-wheelers, and comparable 650b bikes in back-to-back tests, I reckon they're simply faster for my riding style. My Specialized Enduro Elite has been fitted with a 50mm stem, 785mm bar and a 150mm travel KS LEV dropper post to my preferences. The Fox 36 Fork seems noticeably less prone to bushing-bind than the long-legged 29er Rockshox Pike it replaced.

The Ibis 941 front wheel is one of the stiffest (including several 650b wheels) we’ve ever tested, and combined with a stout Super Gravity front tyre, this eliminates any front-end flex which might otherwise distract from what the fork is doing in the turns. The original Roval Traverse rear wheel remains, as a flexy rear wheel is less off-putting, and the greater compliance affords more traction over rough ground. Guide Ultimate brakes provide predictable stopping power, and a Specialized Slaughter Grid allows for plenty of rear wheel steering antics.