Mountain bike racing demands a totally different type of power output from road racing. Here, Jason Hilimire of Colorado-based FasCat Coaching explains the difference between road and mountain bike power, and how you can optimize your training to meet those demands.

How to raise your anaerobic capacity

While road racers need a steady power output, the technical terrain encountered in mountain bike races requires sudden short bursts of energy, often preceded or followed by periods of low power output when the rider stops pedalling to scrub speed or navigate around obstacles.

Therefore, a rider's ability to perform high-level efforts over and over during a mountain bike race is critical. Having a huge aerobic engine is important too, but having both abilities is a lethal weapon.

At FasCat Coaching, we like to have mountain bike athletes perform 'tempo burst' intervals. These consist of the rider pedalling at their standard tempo for two to four minutes and then jumping out of the saddle for 10 to 30 seconds at 125 percent or greater of their threshold power. After the burst, the athlete returns to their standard pace until the next burst. Here is an example tempo burst workout:

- Cycle for nine minutes at standard tempo (224-266 watts if you have a power meter), jumping out of the saddle for 10-second high-power (357w) bursts at the three, six and nine-minute marks. Repeat twice, then continue riding for another nine minutes without any bursts.

As the athlete progresses, tempo burst intervals can be replaced with 'sweet spot' and even 'full gas' intervals, which are more advanced and much harder. Here is an example sweet spot workout:

- Cycle for 10 minutes at a slightly harder pace (245-286w), jumping out of the saddle for 15-second high-power (357w) bursts at the two, four, six, eight and 10-minute marks. Repeat three times, then continue riding for another 10 minutes without any bursts.

The most advanced workout is to perform bursts during a threshold interval. In other words, to go harder when you are already going as hard as you think you can. At FasCat, we reserve the threshold burst intervals for the two to three weeks before a race. Here is an example:

- Cycle for 20 minutes at a hard pace (268-310w), jumping out of the saddle for 15-second high-power (357w) bursts at the five, 10, 15 and 20-minute marks, then continue riding for another 20 minutes without any bursts.

These burst intervals force the physiological adaptations required for the constant start/stop pedaling and short bursts of anaerobic power needed to ride fast over technical off-road terrain.

To work exclusively on your anaerobic capacity, there’s the old tried and true Zone 6 workout. Here is an example:

- Sprint for one minute (357w), then pedal at your normal speed for one minute. Repeat three times. Pedal for five minutes at your normal speed, then do a second set of four 'one minute on, one minute off' intervals.

This workout contains eight minutes (two sets of 4 x 1 minute) of anaerobic capacity work. We adjust the duration on an individual basis between five and 25 minutes, with never more than seven intervals per set. One minute is a good middle-of-range anaerobic capacity duration but 30 to 90 seconds may also be used.

If you want to take your A game up to an A-plus game this season, these mountain bike-specific intervals are just the ticket.

Road power versus mountain bike power

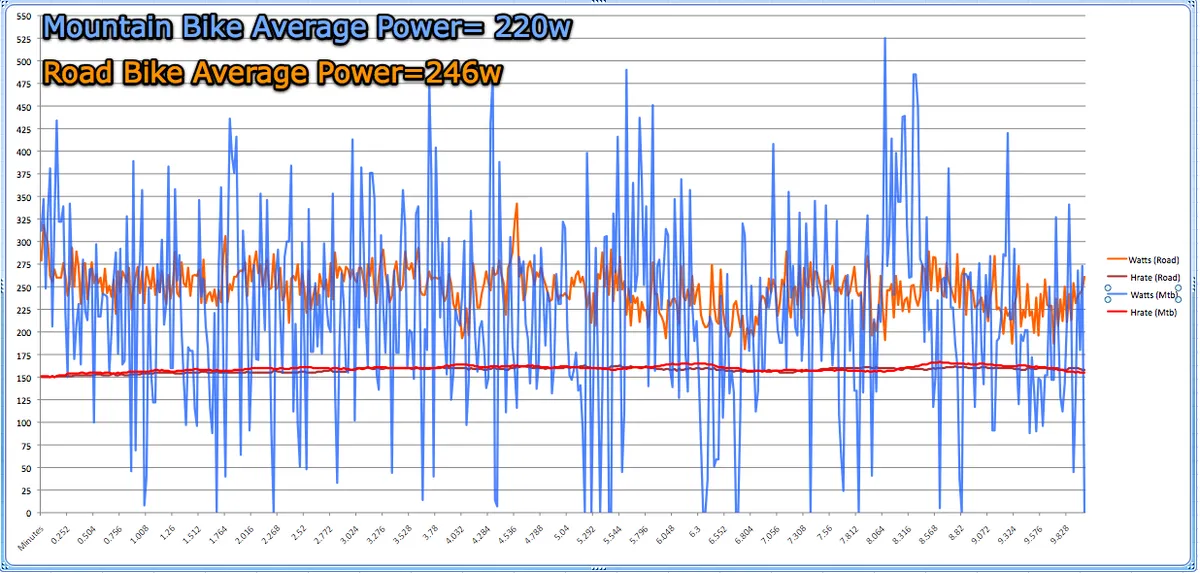

To illustrate the difference between road and mountain bike power, I collected data using a PowerTap power meter on two different 10-minute climbs. The first was on a road bike up a steady two to four percent grade hill. The second effort was on a mountain bike up a singletrack climb with the same gradient. I rode both efforts at the same rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and had an average heart rate of 159bpm for both.

In the graph below (click on the thumbnail below the main image at the top of this article to see a larger version), I have overlaid the road and mountain bike power data on top of each other to see the difference in the two 10-minute climbs. As you can see, the power fluctuated much more during the mountain bike climb than on the road bike.

Average power for the mountain bike effort was 220 watts, while on the road it was 246w. However, there were a dramatic number of efforts above 300w off road, while the road climb needed a much more steady power output, without any forays above 300w.

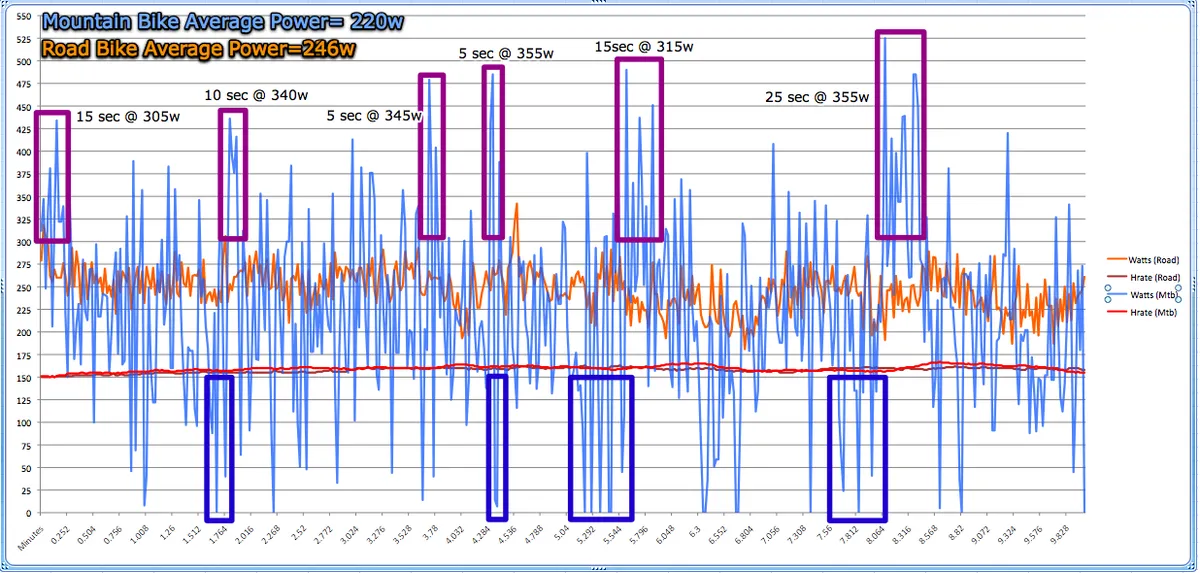

From the power data we can see that this 10-minute singletrack climb contained six sections where it was necessary to produce more than 300w. These short bursts of effort lasted anywhere from five to 25 seconds and are highlighted in purple below.

Short bursts of effort like these occur repeatedly during mountain biking – during a two-hour cross-country race I saw 88 such instances!

Mountain biking’s need for bursts of power is primarily due to the terrain. Rocks, roots, ruts, short steep climbs, switchbacks and other obstacles all contribute to the highly variable power demands. It’s essential to mountain bike racing to be able to produce these efforts in order to clear the technical terrain and maintain your speed.

Conversely, you’ll notice that preceding most of these efforts are periods of zero wattage (highlighted in blue). This indicates that the terrain was fairly technical and I had to stop pedaling temporarily to clear a section of trail. When I started pedaling again I went from 0w to 300w to keep the momentum going.

It’s these short burst efforts and the subsequent changes in wattage or cadence that truly distinguishes mountain bike racing from road racing. Cumulatively, these efforts add up to a big physiological demand. Once or twice is nothing, but 88 times (like in a race) will leave you exhausted.

If you reach that capacity in a race you’ll have no choice but to slow down. However, if you work on raising your anaerobic capacity in training, you’ll have an extra gear to race faster. Much faster.