In our Tech Q&A series, we tackle cycling queries – no matter how complex or trivial – with insights from the BikeRadar team and trusted industry experts. Next up, a reader who hates his knees wants to know how to convert his old bike to singlespeed.

I’ve got an old steel hardtail that I want to convert to singlespeed. What’s the best way to do this?

Thomas Mason

Despite the fact singlespeed mountain biking is, without question, a fundamentally sicko-coded pastime, it has a curiously persistent draw for cyclists.

Who hasn’t dreamed of the tantalising simplicity of doing away with derailleurs while intoxicated by chain degreaser fumes after a disgusting mud-crusted winter ride?

Singlespeed riding also brings a fresh take on cycling, no matter the discipline – the physical challenge of grinding up once-easy hills or maintaining momentum on flowy trails is tremendous fun.

No matter your motivation, there’s more than one way to go singlespeed – and some routes are better than others.

Most of these points also apply to road and gravel bikes, so read on even if you’re not a mountain biker.

Dedicated singlespeed bike

Unhelpfully, the most reliable way to go singlespeed is to buy a proper singlespeed, or singlespeed-convertible, bike.

Unlike a conventional bike, these enable you to either:

- Move the rear wheel fore and aft to tension the chain using sliding or horizontal dropouts, rather than conventional vertical dropouts

- Apply tension to the chain using an eccentric bottom bracket – more on these later

This is preferable because the frame itself is designed to provide proper, fixed mechanical chain tension – eliminating the need for tensioners or compromised solutions.

However, there are relatively few singlespeed mountain bikes on the market – and given you’ve asked how to convert your old bike, we’ll assume you don’t have one.

A note on nomenclature

Note: ‘Vertical dropouts’ isn’t a perfect term. Many, if not most, road bikes of the mid-20th century used semi-sloping dropouts (as pictured), which enabled bikes to be run singlespeed or fixed.

Vertical dropouts took over towards the end of the century – and were the most common option on mountain bikes up to the thru-axle era. These don’t allow fore-aft adjustment of the wheel, which is the key limitation when converting to singlespeed.

Despite the fact a thru-axle is not a dropout in the strictest sense of the word, they're commonly referred to as 'vertical drops'. As such, we’ll refer to all non-adjustable designs as vertical dropouts here.

Sprung tensioner

SQUIRREL_13797961

The next easiest option is to use a sprung chain tensioner. These mount in place of a rear derailleur, with a sprung arm applying tension to the chain via a pulley wheel.

These provide you with a bit more flexibility to swap gears without having to change your chain length. They’re also very easy to live with and quite affordable. This is what we’d recommend for the singlespeed-curious shredder.

However, chain security will not be as good as a proper singlespeed setup offered by sliding dropouts or an eccentric BB.

While the spring is strong, it’s nothing like a clutch-equipped derailleur, and you might find the chain slaps on the chainstays on rough terrain.

The exception to this is the intriguing Reverse Components Collab Pro.

Like a modern rear derailleur, this high-quality, two-pulley tensioner includes a clutch and enables you to adjust the chainline of your drivetrain – more on this in a moment.

SQUIRREL_13797964

Eccentric BB

An eccentric bottom bracket is a neat mechanical workaround for frames that don’t have sliding or horizontal dropouts.

Instead of moving the rear wheel to tension the chain, you move the crankset.

It works by offsetting the bottom bracket spindle from the centre of its outer shell – hence ‘eccentric’, rather than concentric.

When you rotate the eccentric unit inside the frame, the crankset effectively moves slightly forwards or backwards relative to the rear axle. That small change in position is enough to apply tension to the chain.

Because the tension is set mechanically – rather than via a spring – it’s fixed in place once tightened, making it a much more secure solution than a sprung tensioner.

Some dedicated singlespeed bikes, such as the Singular Swift, have true eccentric bottom brackets, with a separate eccentric alloy sleeve clamped into an oversized shell. A conventional bottom bracket then threads into this.

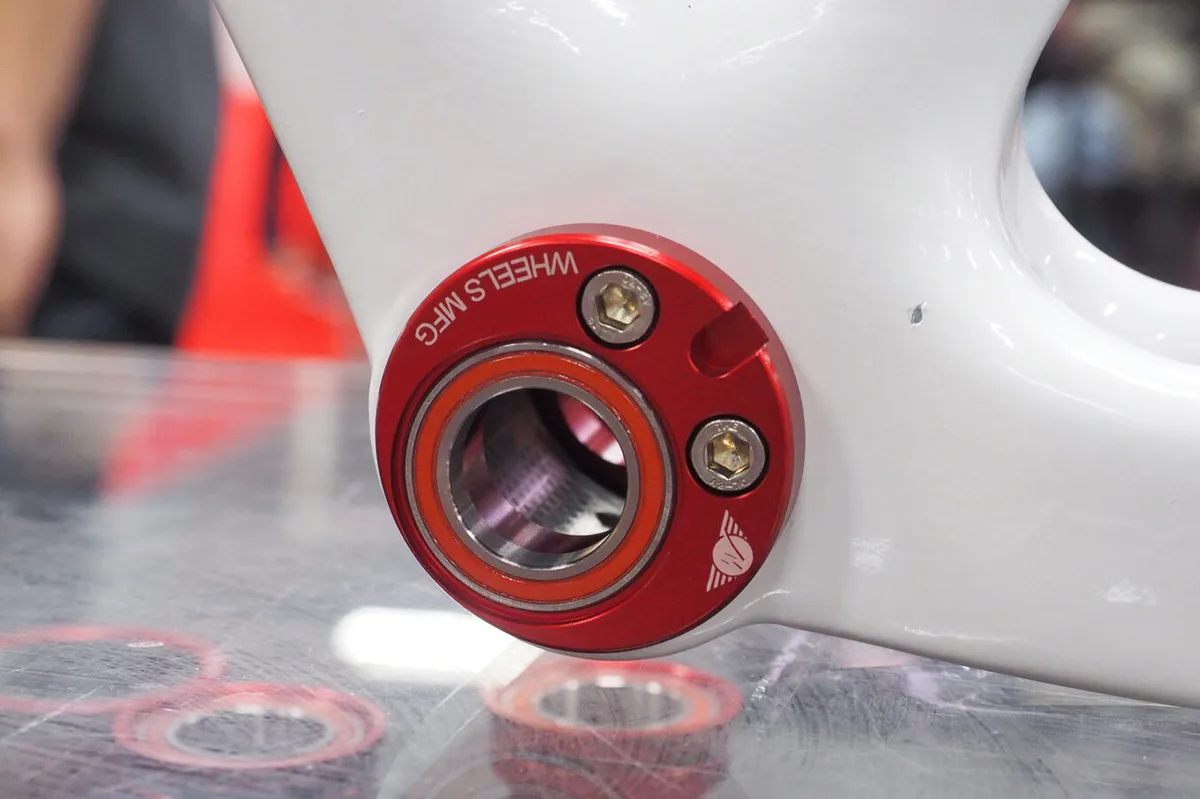

However, it’s also possible to fit an eccentric bottom bracket into a conventional bottom bracket shell.

These replace a standard bottom bracket, with the spindle offset from the centre. The principle is otherwise the same as a true eccentric shell.

However, the throw (how adjustable they are) is limited, so you’ll likely need to swap chains if you switch gears. They are also expensive and quite bulky.

SQUIRREL_PLAYLIST_10208268

Velo Orange, Phil Wood, Trickstuff and others produce eccentric BBs for standard threaded shells. Wheels Manufacturing also produces one for BB30 press-fit shells.

First Components also appears to have offered one for T47 bottom bracket shells, although it looks as though this might have been discontinued.

White Industries’ curious eccentric rear hub bears mentioning. It works in broadly the same manner, but offsets the rear wheel’s axle from the dropout, rather than the crankset.

These are popular with road riders looking to convert their bikes to a fixed gear – another form of gear-restricting fetishism – but aren’t suitable for most modern mountain bikes because they cause issues with disc-brake alignment.

Magic gears

A magic gear setup relies on running a specific combination of chainring size, rear cog size and chain length that just happens to produce correct chain tension on a frame with vertical dropouts – without the need for a tensioner or eccentric bottom bracket.

Since chain pitch is fixed, and because the distance between your bottom bracket and rear axle is fixed, only certain gear combinations will result in a chain that is neither too tight nor too loose.

Many riders use a half link chain – or a single half link in an otherwise standard chain – to fine-tune the fit.

If you get lucky – or spend long enough with a calculator – you can land on one that fits perfectly.

This isn’t a feasible solution in most cases. Tolerances are tight, and even small variations in chainstay length, manufacturing tolerances or chain wear can upset the balance.

You’re also locked into a very specific gear ratio unless you’re willing to swap chains. And if the fit is even slightly off, you risk excessive drivetrain drag from an overtight chain – or the chain derailing if it’s too slack.

Other things to consider

No matter how you tension the chain, you will need to swap your cassette for a singlespeed cog. This is easy with a standard Shimano HG-style freehub, but you’ll need to spend a bit more if you have an XD or Microspline freehub, because options are more limited.

Most, if not all, singlespeed conversion kits enable you to move the cog side-to-side to align the chain with the crankset, providing a straight chainline.

As a final point, unless you use a sprung chain tensioner, the vast majority of full-suspension mountain bikes cannot be converted to singlespeed.

This is because the effective chain length changes as suspension compresses, meaning your chain will either snap or fall off as you ride.

If you are desperate – and odd – enough to want to turn your enduro bike into a singlespeed rig, we’d strongly advise you to stump up for something such as the Reverse Components Collab.