Gravel racing is changing a mile a minute, with everyone struggling to keep pace with innovation.

Some of these trends will come and go, replaced by better data or better arguments, but some of these changes will stay and then trickle down from the high-end racing crowd to everyday riders less obsessed with performance.

To make sense of the noise, here are six trends that I saw on the North American gravel race circuit in 2025 to unpack what’s in, what’s out, and what might be coming next.

Big tyres are here to stay

At this point in time, it’s almost too late to point to gravel’s move towards mountain bike tyres as an active trend. In reality, that pivot has already arrived and companies such as Maxxis, Vittoria and Specialized have built out their gravel-specific tyre options for 45-50mm rubber and beyond. Many of the best gravel tyres are now available in such sizes, even if every rider isn't on board with going wider.

To an extent, the second trend on this list – the rise of suspension forks – is having an impact, too. Where some riders may have been looking towards big, squishy tyres to improve comfort previously, a gravel-ready suspension fork can do the hard yards, negating some of the usefulness of supersized rubber.

Still, don’t expect to see frame clearances drop back down to ‘pre-inflation’ levels. The capacity for big tyres won’t be going anywhere, even if riders settle on a 48mm or 50mm tyre.

The market will continue to fill out with better options for gravel-specific rubber in sizes that were previously thought of as unfathomable. The proverbial cat is out of the bag and, on certain courses, the importance of a fully-fledged mountain bike tyre isn’t going anywhere.

- Read more: I’m a UCI-level gravel racer and this is the big advantage of MTB tyres that nobody is talking about

Suspension forks to smooth the ride

A recurring critique kicking around internet comment sections is that gravel bikes are just early mountain bikes with modern materials. Instead of being something new, they’re recycling the small travel, upright geometry of the mountain bikes from the early 90s.

The increasing number of short-travel, gravel suspension forks take the brunt of these aspersions. Nevertheless, whether bikes sporting these forks are recycled or revolutionary isn’t stopping the gravel suspension movement from creeping towards the norm.

The power of this trend is best exemplified by a few additions to the market, namely the DT Swiss fork built for the Canyon Grail, and released in May 2025.

Before this point, suspension forks were becoming increasingly popular, but were frame-agnostic. The RockShox Rudy XPLR, Fox 32 Taper-Cast and Cane Creek Invert have all been marketed as fitting on several different geo-corrected frames. The DT Swiss/Canyon collaboration, however, is built for the Canyon and is not available to purchase on its own, as it stands.

Like large-volume tyres, these short-travel forks are all geared towards managing the suspension losses of gravel terrain.

Suspension loss is the cost of vertical movement on an object's forward velocity. To put it plainly, the more an object moves up and down, the slower it will move forward. For a cyclist, the suspension losses come from the tyre/ground connection. The more aggressive the movement up and down, the slower the rider will travel forward.

In gravel, wider tyres are faster because they can operate at a lower pressure without flatting. That lower pressure dissipates some of the vertical movement, smoothing out the ride, and preserving momentum.

Crucially, front suspension does this too, and it may even do it more efficiently than a large tyre. Over some courses, we have already seen that pivot being made as the likes of Keegan Swenson, Russell Finsterwald and Haley Smith have all dabbled with these kinds of setups.

- Read more: Lachlan Morton says big gravel tyres and suspension are trying to solve the same problems

Aerodynamics around the edges

In any type of bike racing, aerodynamics is an unavoidable force.

However, track and road cycling are the domains more transfixed by the importance of aerodynamics. Careers have been created, innovation is running rampant, and winning without a deep understanding of aero seems more and more impossible.

Where aerodynamics fit into the gravel equation is a different story.

There are some in the gravel world who have gone all in on aerodynamics. Riders who might not be the best climbers, for instance, are doubling down on the aerodynamic equation as they are building their race programs around punchier races in the windswept American heartland to anchor their competitive pursuits.

Alternatively, those with better climbing chops or technical skill advantages make more considerations geared towards compliance, durability and traction.

Some events cross the Venn diagram – Unbound, SBT GRVL, Midsouth and Big Sugar to name a few – but largely, gravel racing is governed by the need to compromise. Sell out for aerodynamics at your own risk; ignore them at your peril.

With the need for compromises, most of the aerodynamic manipulation has focused on aerodynamics around the edges. Instead of optimising the aerodynamics of frames, wheels and tyres – where the need to change setups significantly between events negates many of the benefits – the aero of everything else has been prioritised.

Aero socks, helmets and skin suits are the norm. Handlebar width, stem profiles and riding positions have also shifted towards aero optimisation. Innovative riders and brands have even found ways to integrate a hydration pack into a jersey. Yet, the big-ticket items at the front of these bike races are still geared towards compliance and functionality (Editor's note: Unless the prototype RockShox fork with aero fairings, used by Keegan Swensen on a drop-bar MTB at the Leadville 100, becomes a production reality...).

It's often a question of losing some of the aero battles to win the larger war.

Lubrication solutions

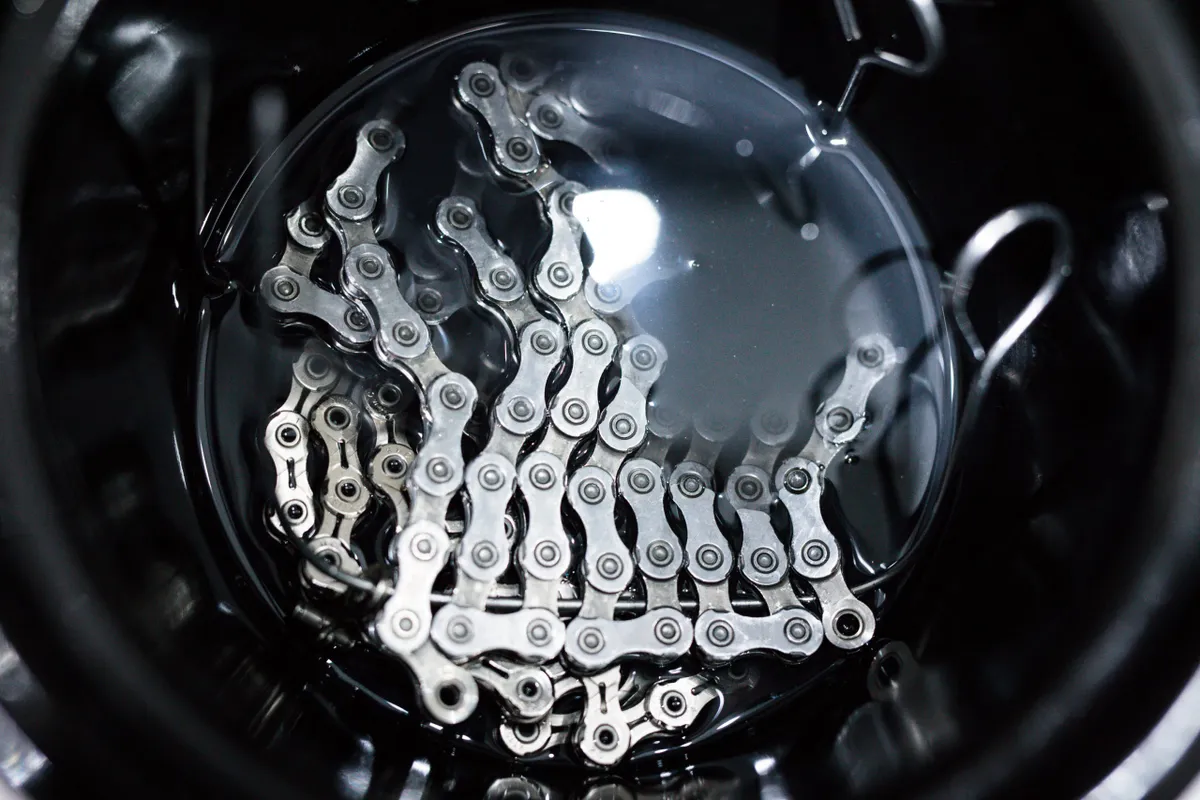

Generally, the biggest trend in drivechain lubrication is the absence of traditional lubricants. Wax treatments have grown in popularity over the last few years, with more and more professionals and amateurs alike opting for a hot wax bath instead of drip oil or wax lubricants of old.

But that isn’t the trend I’m going to highlight here. In fact, I’m going to discuss the exact alternative.

One of the most innovative tech solutions spotted at Unbound this year came from the Canadian LifeTime Grand Prix athlete Andrew L’Esperance and his remote lube applicator.

L’Esperance had tried wax solutions, but for gravel racing, he wasn’t satisfied with the longevity.

What’s more, he found that reapplying a wax lube to a waxed chain was never as effective as just re-lubing a chain that started with a simple wax-based lube.

At Unbound, dusty riding is often juxtaposed to periods of wet mud and creek crossings, which is the worst case scenario for drivechains and is a tough challenge for wax, even if the event is theoretically within the mileage range of most waxes.

What he came up with was a small syringe filled with lube attached to his down tube. That syringe was attached to a tube that ran down his seat tube to the chain, where it deposited lube on the chain as he rode. No stopping, no awkward bending, no aimless spraying.

It is hard to say that this novel solution will come to the masses through a refined design, but that’s not really the point.

The point here is to say that the optimal lube for gravel racing is hardly a consensus, as L’Eseperance was not the only pro who cast doubt on the supremacy of wax on gravel. Even if wax is becoming universal on the road, the direction in gravel among the pros is still conflicted.

Bigger chainrings and shorter cranks

Two of the most noticeable tech shifts in road racing in recent times have been the shortening of crank lengths and the increase in the number of chainring teeth. Both have filtered through to the gravel scene, too.

Thanks to one Tadej Pogačar, the popularity of 165mm or shorter cranks exploded on the road scene. We even spotted Jonas Vingegaard on tiny 150mm cranks for a brief time. Conversely, chainrings have gotten bigger and bigger, with 54, 55 and 56-tooth chainrings growing in prominence in the pro peloton.

There are two primary arguments for shorter cranks: they can help a rider adopt a more compact, aero position, while shorter cranks also help a rider maintain a higher cadence for a given gear ratio. Big chainrings, meanwhile, are more efficient (we've got a full explainer on that) and help a rider to maintain a straighter chainline.

It’s no coincidence that more 48 and 50t chainrings have been strapped to 160-165mm cranks through the 2025 gravel season, even as the wider tyres have increased the gear rollouts of forward-thinking gravel setups.

All this has helped make gravel racing faster than ever, making those big chain rings all the more worthwhile.

Triathlon saddles and progressive positions

Gravel has borrowed from triathlon tech before. In the beginning of its growth in the post-pandemic period, gravel races were often decided between riders with triathlon-esque extensions. These clip-on tri bars were essential for many races, as the aero benefit couldn’t be ignored.

What ultimately came to a head was the debate around safety. Tri-bars, for all their aero benefit, have always been excluded from draft-legal racing, including Olympic triathlon racing.

Fierce internet debate ensued, and slowly aero bars began to be phased out as races set their own rules against TT-style extensions, including the biggest race of them all, Unbound in 2023.

Nevertheless, triathlon tech has begun to ease its way back into gravel racing through triathlon-optimised saddles and their ability to support progressive, aero positions.

Offerings from ISM, Pro, Ergon and Wove that began as triathlon products have begun to pop up among gravel racers. These saddles are popular as they support both riding on the nose of the saddle – pitched forward to close a rider’s frontal area – and sliding back to the rear of the saddle for comfort in a pack or on a climb.

While this is far from uniform, as the speed of gravel races continues to rise, so too will the developments around aerodynamic body position. When that happens, more and more triathlon options will look like the right solution for pro-level racers.