World Cup-style downhill mountain bike racing today is an awe inspiring display on courses that are both very fast and extremely demanding technically. The early days of the sport, however, more closely resembled downhill ski racing with one major goal: outright speed. And no event epitomised that period better than the Kamikaze at Mammoth Mountain, California.

The Kamikaze course is at its heart little more than a fire road that provides maintenance access to the mountain's various features. Compared with modern World Cup courses, that thoroughfare was wide open and comparatively free of significant obstacles, which made for some staggering speeds. Top riders regularly crested 100km/h (62mph) – and as you would imagine, crashes at those speeds were less than pleasant.

It's amazing to think about how fast riders were going on bikes like this back in the day

Much as the discipline of downhill racing was in its infancy at that time, so, too, was the equipment that the racers used to hurtle themselves toward the bottom of the mountain.

Kurt Stockton was a US-based pro in the mid-90s racing for Kestrel – then one of just a handful of companies offering carbon composite frames. While Kestrel may have been considered to be ahead of the curve in many ways at the time, the Rubicon Comp chassis that Stockton used was a far cry from the highly evolved, purpose-built downhill rigs of today.

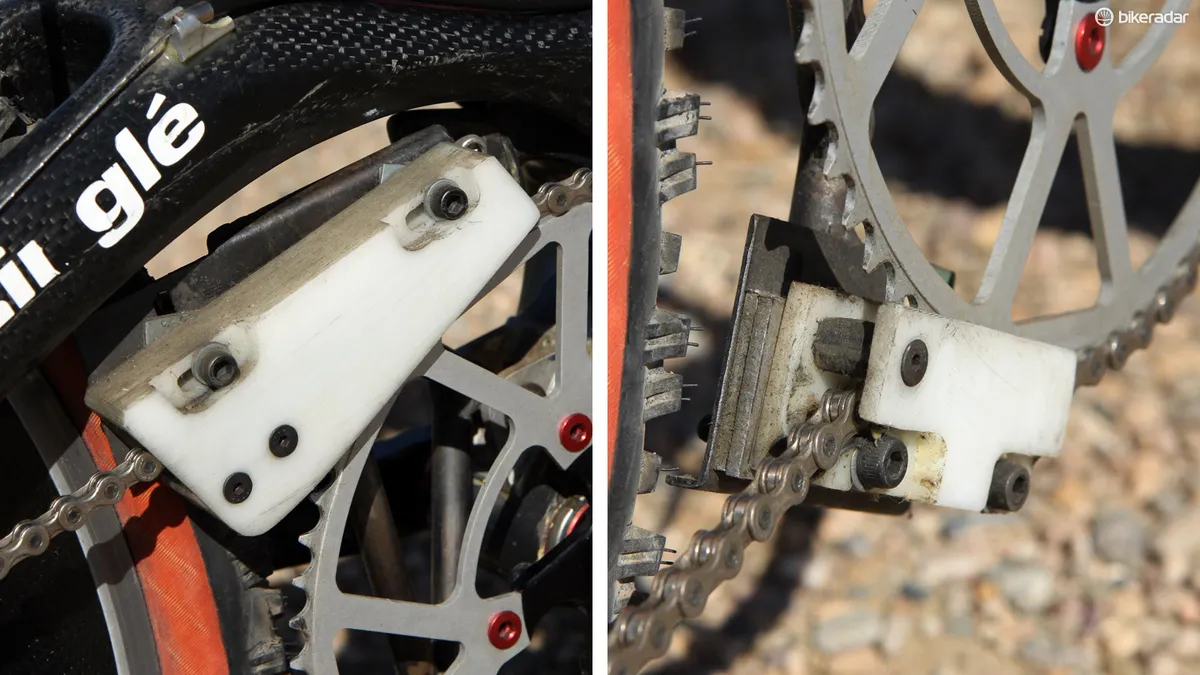

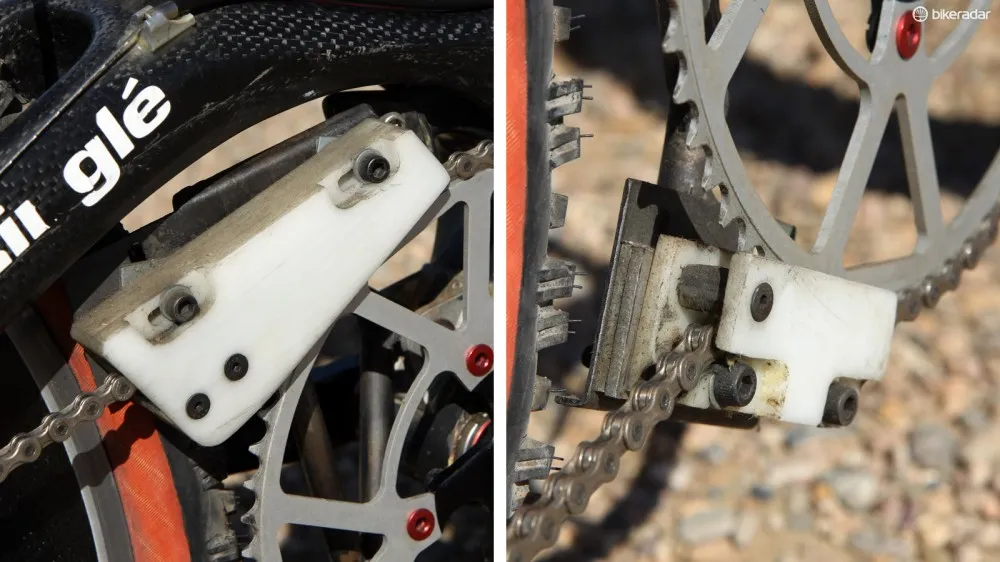

Chain retention was especially challenging in the early days of DH, especially given the lack of refined solutions

Kestrel designed the Rubicon Comp as a cross country bike, complete with about four inches of front suspension travel and nearly five out back courtesy of a modified high single pivot layout. A link connected the swingarm with the articulated top tube so that when the rear wheel went up, the saddle went down.

The angles were steep, the wheelbase was short, there was no provision for any sort of chain retention, and speed control came courtesy of two pairs of rubber blocks that were squeezed against the rim. Both wheels were attached with quick-release skewers.

The RockShox Judy DH was state-of-the-art in the mid-90s but few would consider it even for rigorous XC riding today

Not surprisingly, it wasn't inherently suited for downhill racing.

The first modification made to get it to that point was to the rear suspension.

"We were playing around with that bike and I was looking at the linkage one day," Stockton told BikeRadar. "I said, 'You know, that rear link looks like the same exact length as the shock we're using.'"

As it turned out, Stockton was right and by replacing that rigid link with a second shock, the rear travel nearly doubled from its original 4.5 inches.

If one shock is good, two must be better, right?

That additional travel – and more importantly, the additional sag – also served to slacken the angles a bit for additional stability. A 63-tooth chainring was fitted to better suit the Kamikaze's ridiculous speeds, a fully bespoke chain guide was made out of welded steel and machined nylon, the aluminium riser bar was reinforced with a bolt-on brace, and Magura hydraulic rim brakes made the most of the available friction. While Stockton mostly raced on Mavic rims, he at times also used HED's ultra-rare deep-section carbon-and-aluminium rims laced on to Ringlé hubs, all shod with similarly rare (for the time) Michelin downhill-specific rubber.

Modern downhill gear is fully dedicated equipment while, despite the extensive modifications, Stockton's bike was still ultimately an XC rig – and like many DH machines at the time, it performed accordingly.

Disc brakes were still a long way from being common in the mid-90s

"It was designed to be a cross country bike," Stockton told BikeRadar. "We threw these two shocks on this thing and it laid back the angle a lot more but the head angle still wasn't slack enough. In the steep stuff – and we did have some, not like it is now, but still – it was a big problem that we dealt with."

Even the positions riders used differed massively from what would be considered typical today. Back then, the courses were much longer – some nearly fifteen minutes in duration – and there was much more pedalling involved. Stockton's handlebar is just 620mm wide, the stem is 120mm long, and the XC-length seatpost sticks way out of the frame.

The bars would be considered unusably narrow by modern standards

"We were still looking at modifying cross country or even road positions for downhill rather than looking at it completely differently. I was totally skewed from racing on the road. We were still trying to run our seats high so we could pedal because there was a lot of pedalling on these courses."

Then there were perpetual issues with reliability. Though the courses often weren't insanely technical, there were still a lot of forces applied given the speeds.

Though the science was perhaps a little lacking, companies at least had an idea what helped riders go fast

"The equipment was road stuff that was being modified," Stockton said. "It just wasn't beefy enough. They got it to work on cross country bikes but for downhill, it wasn't there. We were blowing shocks out, blowing forks out all the time, and that was it."

Stockton's frame was even fitted with a fully custom swingarm with additional plies of carbon fibre after the original one broke.

The carbon swingarm is a handmade one-off

Even though the bike was essentially a beefed-up cross country model, it still wasn't exactly light, either. As shown here, Stockton's Kestrel weighs in at 15.34kg (33.8lb) and that doesn't include the much heavier downhill inner tubes he used to use or pedals of any sort. For reference, Greg Minnaar's current Santa Cruz V10 comes in at 15.08kg (33.18lb) complete.

Despite that extra weight, Stockton recalled that riding that modified Rubicon Comp was anything was confidence inspiring at those speeds and on that terrain.

"It was sketchy but it was like, we were all doing it. I remember going off the top of Mammoth and you're going 50, 60 miles an hour. You just hung your ass off the back, kept your hand off the front brake and you just went. That was it! It was just, go for it."

"At 60 miles an hour on a really nice road bike on smooth pavement, you've got to be attentive, right? We were riding down a bunch of pumice where you're basically just floating on the marbles. It was all just kind of a controlled power slide the whole way down. As long as you kept air in the front tyre, it was ok."

Special thanks to the folks at The Pro's Closet, who will soon open up a museum of noteworthy vintage bikes at their headquarters in Boulder, Colorado.

Complete bike specifications

- Frame: Kestrel Rubicon Comp w/ custom rear swingarm, dual shocks

- Rear shock: Fox ALPS 4, Fox ALPS 4R

- Fork: RockShox Judy DH

- Headset: Chris King GripNut, 1 1/8in threaded

- Stem: Ringlé Zooka, 120mm x 10°

- Handlebars: Custom 3T aluminium riser, 620mm

- Tape/grips: Pedro's Blackwalls

- Front brake: Magura HS-22

- Rear brake: Magura HS-22

- Brake levers: Magura HS-22

- Rear derailleur: Shimano Deore XT RD-M737-SGS

- Shift levers: Grip Shift X-Ray

- Cassette: Shimano XTR CS-M900, 12-30T

- Chain: Taya

- Crankset: Ultimate Machine, 175mm, w/ 63T Avitar chainring

- Bottom bracket: Ultimate Machine

- Rims: HED Downhill, 32h

- Front hub: Ringlé Super Bubba, 32h

- Rear hub: Ringlé Super Eight, 32h

- Spokes: Bladed stainless steel, 32h, 3-cross

- Front tyre: Michelin Service Course DH, 26 x 2.2in

- Rear tyre: IRC Mythos XC, 26 x 2.1in

- Saddle: Selle San Marco Bontrager No-Slip

- Seatpost: Ringlé Moby

- Other accessories: Bullet Brothers chain tensioner, custom chain guide