Aero wheels are faster on the flats, lightweight wheels are faster on the climbs. That’s the accepted wisdom.

But what exactly are the differences in the real world, for a normal rider? Does rotating weight actually matter on climbs? Are the endless manufacturer claims about aero wheels true?

I’m going to show you the differences based on real-world testing, performed at an outdoor velodrome and on a brutal climb in South Wales.

I’ve long said I can feel the difference aero wheels make on a bike, and that lightweight wheels don’t make much difference even on climbs.

This is the first time I’ve put those things to the test in a controlled manner, though.

Let’s find out what the truth is.

The wheels

To help us answer these vital questions, Hunt kindly loaned us two sets of fancy carbon fibre wheels; the 60 Limitless Aero Disc and the 32 Aerodynamicist UD Carbon Spoke Disc.

The aero-optimised 60 Limitless wheels use a progressive, ultra-wide design, with a 60mm-deep and 34mm-wide rim.

The claimed weight for the wheelset is 1,669g. Not bad for an aero wheelset, but certainly not ultra-light.

The 32 Aerodynamicist UD Carbon Spoke Disc wheels, on the other hand, are designed to be as light as possible.

They use a shallow, hookless carbon rim, which measures 32mm deep and 25mm wide. They also have carbon fibre spokes, which are said to be both lighter and stiffer than conventional steel spokes.

All in, the lightweight wheels are claimed to weigh 1,213g – around 450g lighter than the aero wheels.

For the tests, both wheelsets were set up tubeless with 25c Schwalbe Pro One TLE tyres, and with the same Shimano disc brake rotors and cassettes to keep the test fair.

The testing protocol

While it would have been possible to get more precise aerodynamic data from a wind tunnel, or to simply calculate what difference a certain amount of weight makes on any given hill using mathematical equations, testing in the real world helps bridge the gap between theory and practice.

To tease out the differences between the wheelsets, I settled on A/B testing. As the name suggests, this involves doing one test run on setup A followed by another on setup B.

For the purposes of this test, setup A was the lightweight wheels and setup B was the aero wheels.

When performing A/B testing, it’s key that variables other than the one being tested are kept constant. This is what enables you to determine that any differences in performance are a result of the one thing that was changed, and not something else.

In this instance, therefore, that meant only changing the wheelsets between test runs and keeping everything else – the tyres, the bike setup, my riding position, cycling kit, my weight, and so on – as consistent as possible.

Of course, some variables, such as the weather, are not within my control when testing in the real world.

Variables such as small changes in temperature can be accounted for (if monitored) because they have fairly predictable effects on performance.

Higher temperatures, for example, decrease air density and rolling resistance, and vice versa.

On the other hand, windy conditions can be highly variable and are difficult to account for.

Testing on days when the weather is relatively calm and consistent is therefore vital to minimise these effects.

Velodrome testing

On the flat, the main forces slowing you down are rolling resistance and aerodynamic drag.

It stands to reason then, that with the same tyres, aero wheels ought to be faster than lightweight wheels.

But with many brands performing their aerodynamic testing at speeds that are arguably realistic only for professional riders, do those effects still benefit regular riders?

To find out, I went to Maindy velodrome in South Wales, where the likes of Geraint Thomas, Luke Rowe and Owain Doull cut their teeth as young stars.

I rode a series of back-to-back laps on each wheelset, at a target average power, and noted the difference in speed between each set.

Everything else was kept as consistent as possible, to ensure any performance differences were the result simply of changing wheelsets.

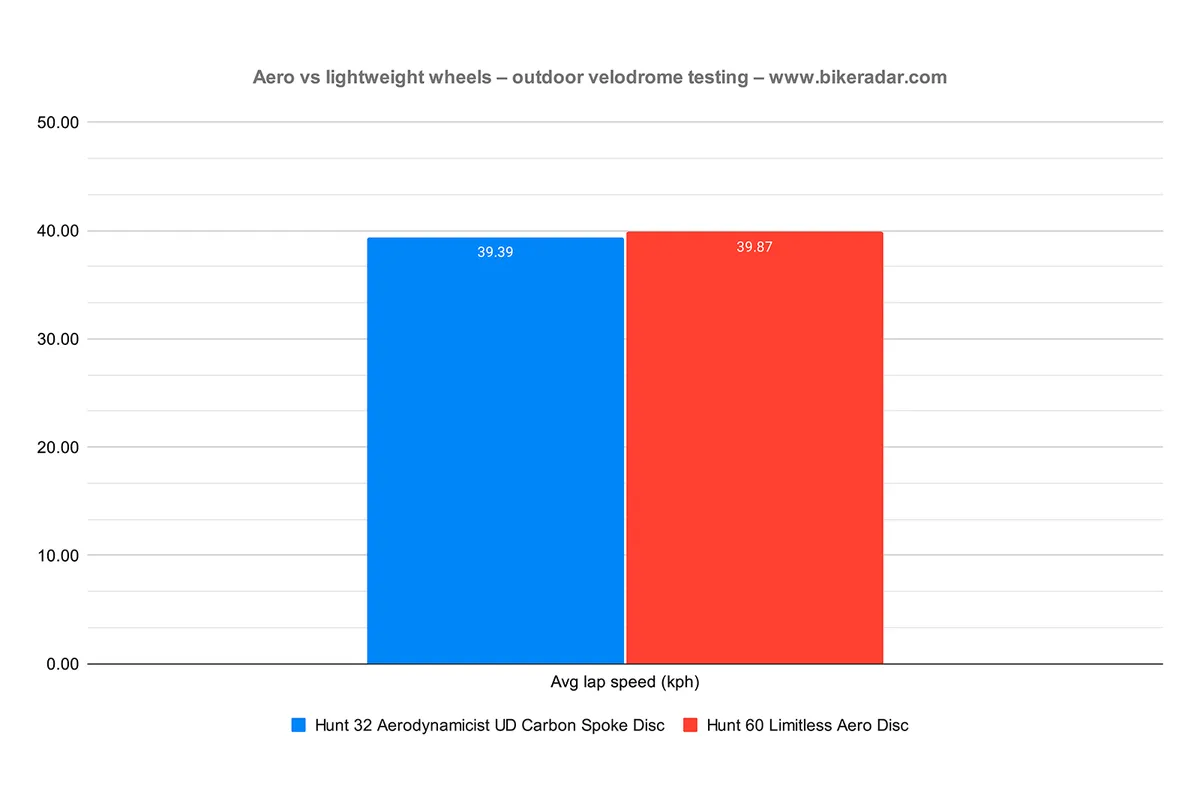

Velodrome testing results

| Results – velodrome testing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunt 32 | Hunt 60 | Difference | Per cent | |||||

| Avg lap time (secs) | 42.66 | 42.09 | -0.57 | -1.35 | ||||

| Avg lap speed (kph) | 39.39 | 39.87 | 0.48 | 1.22 | ||||

| Avg lap power (watts) | 241.7 | 245.87 | 4.17 | 1.73 | ||||

| Avg temperature (C) | 26 | 24.7 | -1.3 | -5.02 | ||||

Having done more than 20 laps on each wheelset, the difference between the two seems to be around half-a-second per 460m lap on the velodrome’s moderately banked track.

Of course, there are some environmental variables here in the real world, and I’m not a robot capable of riding at a precisely set power output over every lap.

However, I did four different sets of laps on each wheelset, over a number of hours and the trend was consistent.

While my average power for the laps on the aero wheelsets was 1.73 per cent higher, the average ambient temperature for those laps was also 1.3 degrees lower, which evens things out a bit.

As with any real-world testing, getting perfectly precise data is difficult and my results are ballpark figures rather than iron-clad guarantees.

At this point, though, you might be thinking, “Half a second per lap? Is that it?” Well, yes and no.

A lap at Maindy velodrome is around 460m, depending on what line you take. Given that, we can say you’re gaining roughly a second per kilometre.

Extrapolating out, we get a difference of around 40 seconds over 40km, or 25 miles – which suddenly seems like a much bigger gap.

So, yes, aero wheels are measurably faster on the flat.

The key takeaway, though, is that what initially seems like a small difference can add up to a significant gain over time.

Climbing test

However, what about in the hills? Lightweight wheels might be slower on a completely flat course, but surely lightweight wheels are faster when you’re climbing?

The chosen test climb is 1.8km long, has an average gradient of around 11 per cent and maxes out at nearly 14 per cent towards the top.

If there’s anywhere a lightweight wheelset should shine, then, it’s on a climb such as this.

With the 34x28t lowest gear I had, simply riding up it in a consistent manner required around 300 watts / 4.5 watts per kilogram for just under 9 minutes, at an average cadence of 78rpm.

That’s pretty much a maximum effort for my current fitness level (where’s Tom Bell when you need him?).

Easier gearing would have been a smart decision, clearly, and shows the impact other tech choices can have in making climbing more comfortable and, potentially, faster.

The longer interval time on the climb, versus the track, makes any differences easier to pick out (because there’s more time for any advantage to accumulate).

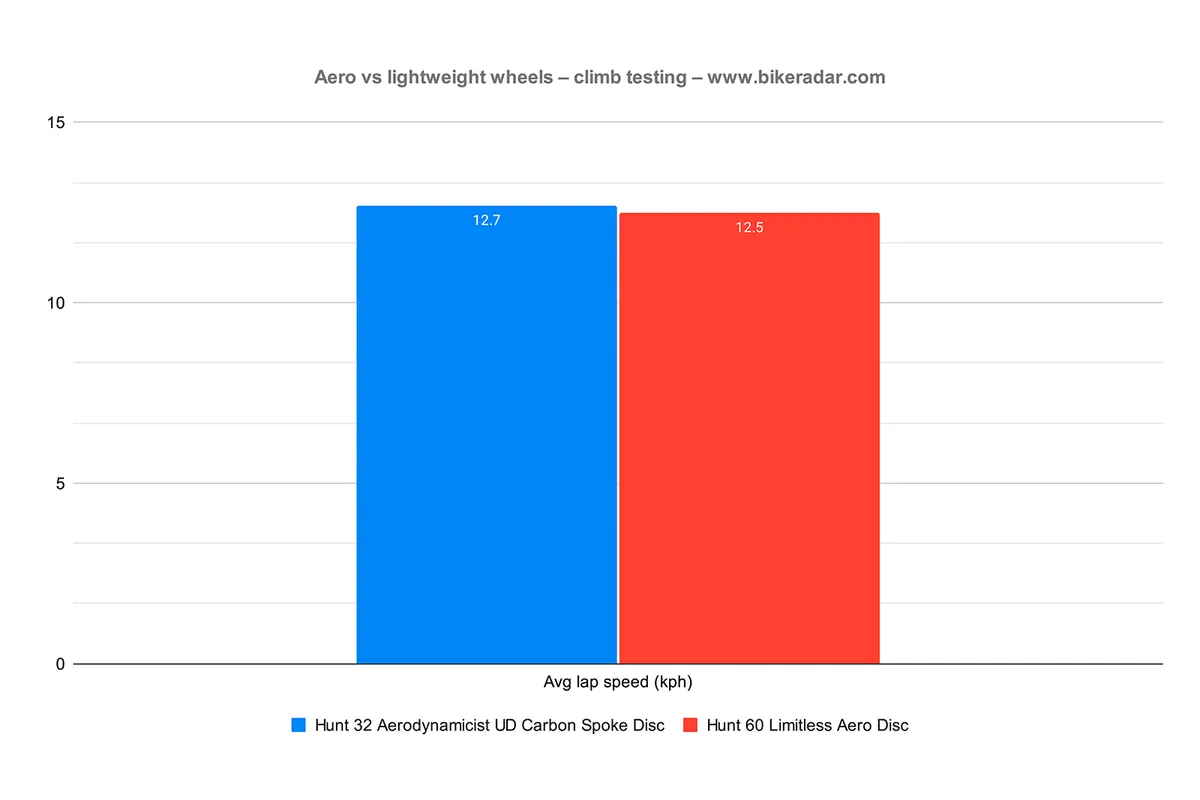

Climbing test results

| Results – climb testing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunt 32 | Hunt 60 | Difference | Per cent | |||||

| Avg lap time (secs) | 532 | 540 | 8 | -1.5 | ||||

| Avg lap speed (kph) | 12.7 | 12.5 | -0.2 | 1.57 | ||||

| Avg lap power (watts) | 307 | 301 | -6 | 1.95 | ||||

| Average temperature (C) | 28 | 26 | -2 | -7.14 | ||||

On this climb, the lightweight wheels were faster than the aero wheels by 8 seconds, which is around 4 seconds per kilometre.

That margin is likely slightly flattering on the lightweight wheels, because my average power during the run with the aero wheels was 1.95 per cent lower and the average ambient temperature had dropped a couple of degrees.

Again, we can view this result in two ways. On the one hand, the aero wheels come impressively close to the lightweight wheels even when the scales are tipped heavily against them.

On the other hand, 2-3 seconds per kilometre on a steep climb could easily make a decisive difference in a hill climb race, or when chasing a Strava KOM/QOM.

As with the velodrome testing, if we extrapolate a small time saving in the region of a few seconds per kilometre to a longer climb of a similar profile, then we are potentially looking at an even more significant time gap.

What type of wheels are best for you?

As most would have likely guessed, aerodynamic wheels are indeed faster on the flat than lightweight wheels and lightweight wheels are faster than aero wheels on steep climbs.

That might not be news to you, but hopefully you now at least have a much better idea of what the potential differences are in the real world.

So which type of wheelset is best for you? Well, the answer to that is complicated.

If you live somewhere like the UK, where we don’t have many super-long, steep climbs, then you’re almost certainly going to be faster overall with an aero wheelset.

While you might give up a few seconds on the mostly short, sharp climbs we have in the UK, you'll likely be spending most of your riding time on relatively flat or rolling terrain, and will therefore have more to gain from an aero wheelset.

Even if you live somewhere with long climbs, you also have to consider the varied terrain – descents and valley drags, for example – you’re likely to encounter on any given ride.

However, if you’re interested in chasing the fastest climbing times possible (or simply being the first of your friends up every hill), then a lightweight wheelset might be the better choice.

There’s also handling to consider. While modern aero wheels typically handle exceptionally well compared to past designs with narrow V-shaped rims, there’s no denying that, for some riders, wheels with shallower rims handle even better on windy days.

The aero wheels might theoretically be faster everywhere except the climbs, but if you’re having to ride more carefully because you’re worried about sudden gusts of wind then you might not see the benefits.

As always, then, a careful analysis of your riding style and goals will help you decide which tech choices are right for you.

Of course, there’s also the option of picking something of an all-rounder wheelset that sits somewhere in the middle of the two extremes, if you want something that can perform well on all terrains, even if it’s not the outright fastest choice in any specific situation.

For more on this topic, check out our buyer’s guide to road bike wheels.