Real-time blood glucose monitoring is claimed to help endurance athletes better understand their carbohydrate requirements and tailor their nutrition accordingly to optimise performance.

However, doubts have been raised about the accuracy of blood glucose sensors during exercise and the value of recording blood glucose for non-diabetic people.

Drawing on my own use of continuous glucose monitoring technology, interviews with athletes and nutrition experts, and scientific research, I’ll assess its potential merits for cyclists.

What is continuous glucose monitoring?

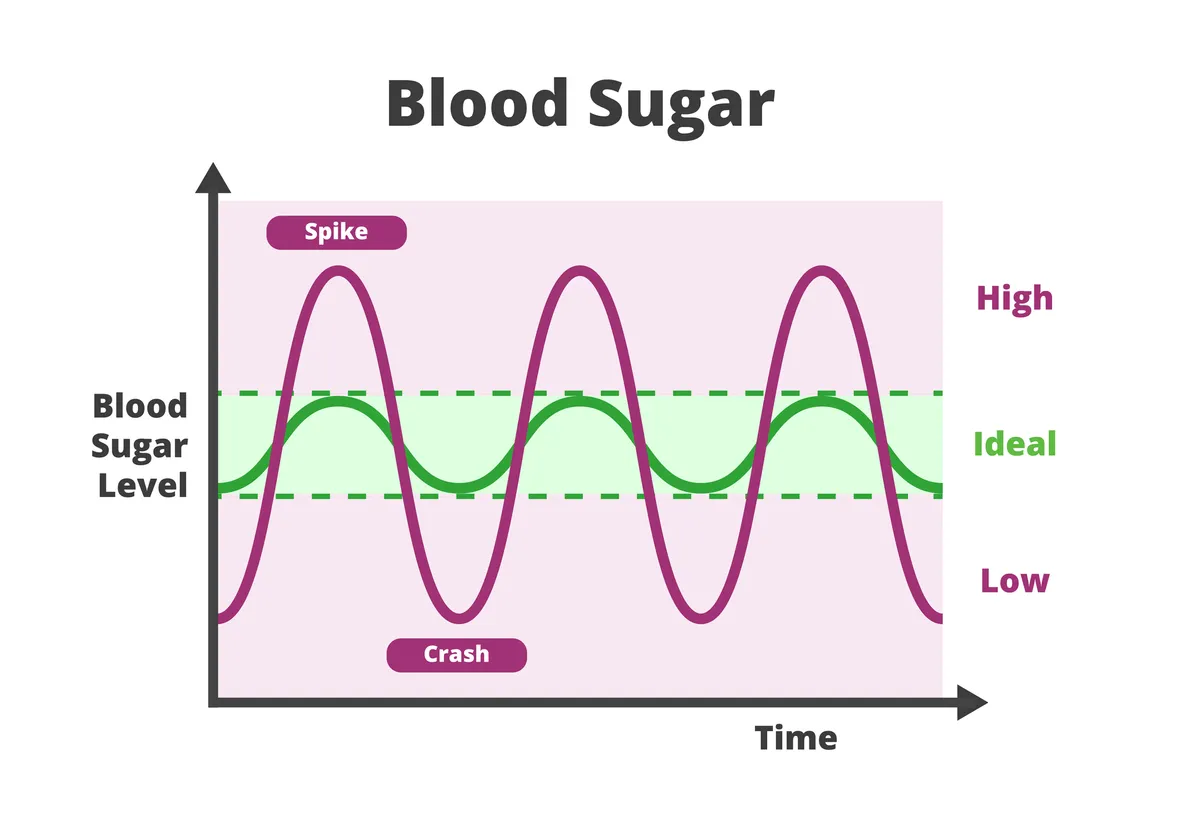

Blood glucose is sugar carried in the blood to the cells and muscles to be used as energy.

In general, you want to avoid low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) and high blood glucose (hyperglycemia).

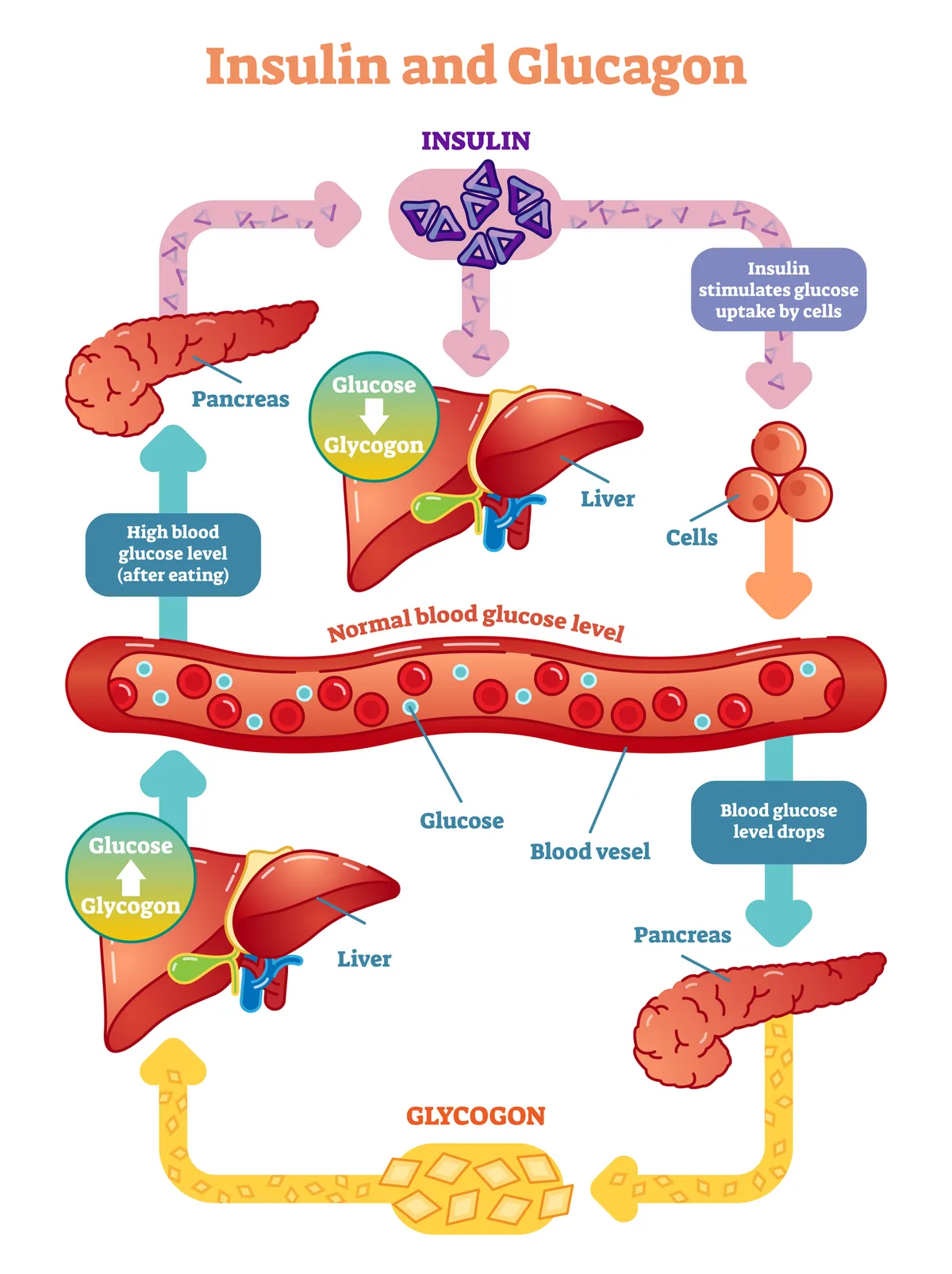

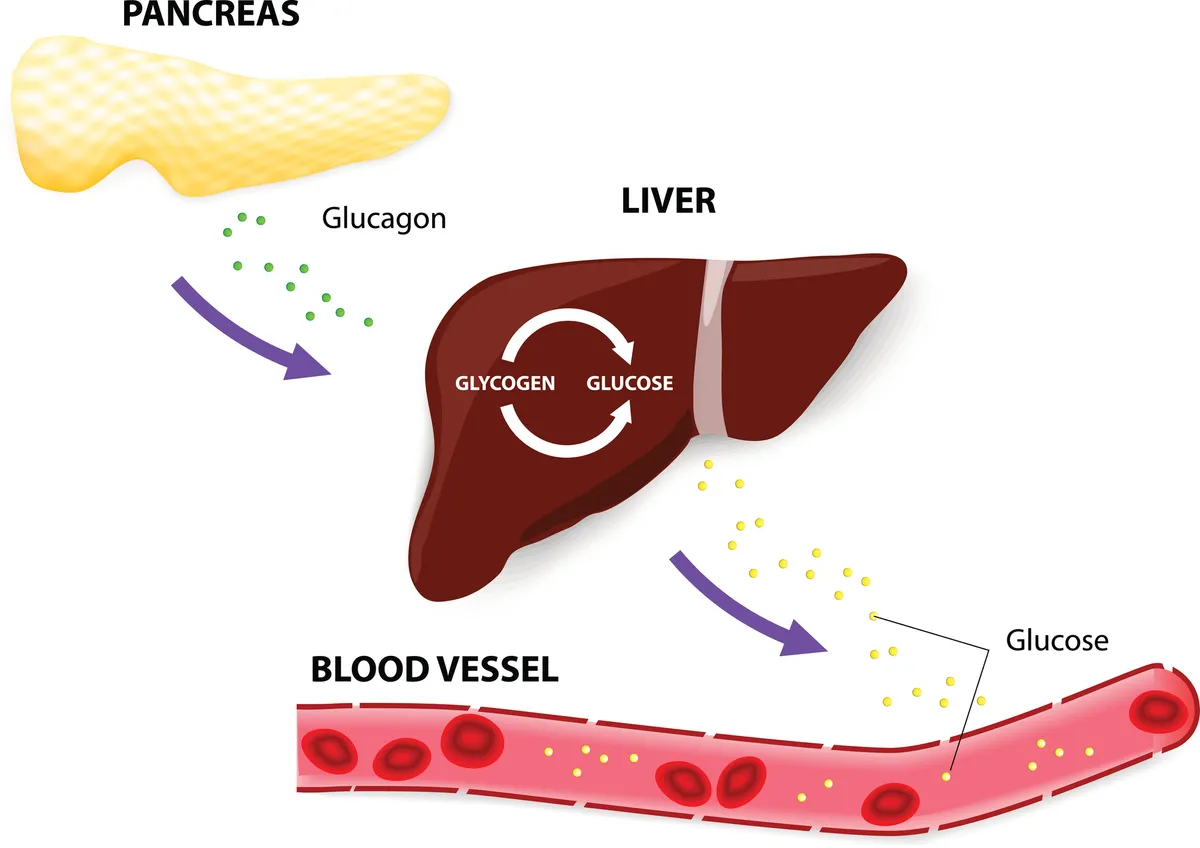

The body has a complex system in place to keep blood glucose constant.

This system is impaired in type 1 diabetics. Their pancreas does not produce insulin, which controls blood glucose in healthy people.

A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) is designed to help users stay within a healthy range.

Until recently, only diabetics used CGMs, but they have gained some mainstream appeal.

Continuous glucose monitoring for non-diabetics

Supersapiens sensors were photographed on the arms of WorldTour cyclists before the American brand ceased trading in March 2024.

Plenty of other CGMs are available though, from companies including Veri, Lingo and Levels.

These companies say non-diabetics should also track their blood glucose because impaired blood glucose control (or insulin resistance) is linked to metabolic syndrome. This can cause cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer.

Continuous glucose monitoring isn’t cheap. Most subscriptions cost between £100 / $100 and £150 / $150 a month.

In the US, CGMs are only available with a prescription, but anyone can buy one in Europe and Canada.

How do continuous glucose monitors work?

Continuous glucose monitoring systems comprise a blood glucose sensor that sends data to an app and sometimes a wristband.

Using a device a bit like a stamp, you press the sensor against your skin, usually on the back of your upper arm.

A needle pricks the skin to insert a smaller needle called a filament. The larger needle retracts, leaving the filament to measure glucose levels in the interstitial fluid, where nutrients are transported between the cells under your skin.

Concentration of glucose in the interstitial fluid is assumed to equal that in the blood. However, there is a lag, which, as I’ll get on to later, is problematic during exercise.

An adhesive patch holds the sensor to your arm. You then pair the sensor, which contains an NFC chip, with the app to transfer data via Bluetooth to your phone and/or a wristband.

The sensor tends to last for 14 days, when you can peel it off and reapply another if desired.

Do healthy athletes need continuous glucose monitoring?

There is a strong case for diabetics to use CGMs, especially when they are exercising.

They enable diabetics to continuously track their blood glucose. This is more convenient than taking regular finger-prick blood samples.

Team Novo Nordisk, an all-diabetic professional cycling team, uses CGMs to race at UCI Pro Team level.

The riders wore Dexcom CGMs before switching to Supersapiens in 2019, when the team's co-founder Phil Southerland set up the company.

In 2021, Supersapiens became the first company to pitch CGMs to endurance athletes. It claimed monitoring blood glucose levels in real time helps athletes fuel better to improve performance and recovery.

Banned but not proven to be effective

Later that year, the UCI banned the use of CGMs in competition by non-diabetic riders. Explaining the ban, the UCI’s Mick Rogers said: “The fans don't want to see Formula One in bike racing, they want surprises, they want unpredictability.”

The cycling governing body’s head of road and innovation added: “We feel that putting such powerful information into the hands of younger riders is taking away a skill [from the rider] – deciding when you need to eat and learning about your body.”

Although the UCI often bans things that improve performance, there is little evidence that CGMs benefit people with normal levels of glucose control.

In an opinion piece in the Sports Medicine journal in 2023, Mikael Flockhart and Filip Larsen wrote that “well-defined approaches to use glucose monitoring to improve endurance athletes’ performance and health are lacking”.

In my experience of using Supersapiens for a month, a user would be forgiven for thinking there is. The brand’s USP was that keeping your blood glucose within a certain range helps you perform better.

And Flockhart and Larsen argue that well-trained endurance athletes effectively regulate blood glucose during exercise.

Their ability to use fat for fuel keeps their blood glucose lower than untrained athletes at low intensity. When intensity increases, well-trained athletes’ blood glucose rises higher than in less fit people, in order to meet the muscles’ demands.

So it’s possible that CGMs could be more beneficial to recreational athletes, but this hasn’t been studied yet.

A flawed measure?

Blood glucose may not be an especially useful metric for endurance athletes to measure.

Research into marathon runners in the 1920s linked low blood glucose to fatigue.

But in New Horizons in Carbohydrate Research and Application for Endurance Athletes, Podlogar and Wallis note hypoglycemia can, but doesn’t always, predict failure in endurance sport. For example, blood glucose can increase before someone is unable to complete a high-intensity interval.

CGMs have shown fluctuations in endurance athletes’ blood glucose are greater than in sedentary people.

Podlogar and Wallis add that tracking blood glucose could be beneficial if further research finds these fluctuations “have some negative effects on athletes’ function”, such as recovery.

Glycogen over glucose

But the proportion of its energy the body stores as glucose is quite small. Only 4g of glucose circulates in the blood of a 70kg person.

By contrast, 100g of glycogen, which can be converted to glucose, can be stored in the liver and 400g in the muscles.

Other research by Podlogar suggests muscle glycogen levels are a better predictor of fatigue than blood glucose.

Dr Podlogar’s 2020 study into carbohydrate feeding and recovery shows glycogen stores start to deplete during prolonged exercise, such as three-hour rides. This happens before blood glucose plummets and you bonk.

Sports nutritionist Ellen McDermott, from McD Nutrition, agrees, adding: “If they [CGMs] could measure muscle glycogen that would probably be better.”

Not accurate enough to be used in exercise

The validity of the data produced by CGMs has also been brought into question.

In a 2022 article published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, Clavel et al tested the accuracy of data from the Abbott FreeStyle Libre sensor, as used by Supersapiens, Lingo and Levels.

They found that during exercise, the CGM displayed a large degree of error, which carbohydrate intake exacerbated.

McDermott has herself found the Supersapiens biosensor “really temperamental”, especially in the cold and when riding or running without a phone.

Implications for real-time blood glucose monitoring

This research undermined the key selling points of CGMs for endurance athletes: the ability to monitor blood glucose during training.

When I did this by syncing Supersapiens with my bike computer, I barely looked at it.

Because I was already training with power and heart rate, I was overIoaded with numbers.

US gravel racer Lauren De Crescenzo told me she found Supersapiens useful in training and in non-UCI events she competed in. However, as a former data scientist, she’s much better qualified than most CGM users to interpret the numbers.

“I don't think it really helps me as much in the event as it does in the days leading into an event,” she says.

“I find it more useful when I’m pre-loading my glycogen stores.”

The quantity and timing of pre-ride fuelling

Researchers also have written that CGMs could help athletes to carb load.

Before a race such as Unbound, which she won in 2021, De Crescenzo says she has used continuous glucose monitoring to keep her blood glucose consistently high.

Wearing a CGM could also stop you suffering a bonk caused by eating too much, too close to a bike ride.

“One big change I did make is to let my breakfast digest for two to three hours, so my glucose stabilises before I start training,” says De Crescenzo.

“If you eat and then run out of the door, you can bonk for no reason.

“Your glucose spikes when you eat breakfast and goes all the way down because your body produces insulin.”

If this hypoglycemic event happens while cycling, you’ll suddenly lose energy.

De Crescenzo adds: “So you need to let it come back up and stabilise before starting a ride.”

Can CGMs stop you from bonking?

The LifeTime Grand Prix racer adds that checking her blood glucose, particularly in ultra-endurance races, has helped her avoid bonking.

That said, the technology behind real-time blood glucose monitoring is potentially flawed.

McDermott says: “The transmission is a bit delayed, so if you're already heading into a glucose dip, it's bloody well too late for you.

“So the best thing is to know your carbohydrate requirements and then fuel accordingly.

“Just have a little reminder on your Garmin that beeps and says 'drink'.”

Can continuous glucose monitoring prevent underfuelling?

If CGMs can’t accurately record blood glucose during exercise, could their reasonable accuracy at rest help you fuel better?

Potentially.

Low blood glucose levels were linked to low energy availability in a 2003 study by Loucks and Thuma. A severe, long-term energy deficit can lead to Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, a serious condition that can lower bone density and stop periods in women.

In addition, Tornberg et al found in a 2017 study that female endurance athletes with symptoms of low energy availability have low blood glucose while fasting and exercising.

Based on this evidence, Flockhart and Larsen argue that “glucose measurements can be used as a marker of reduced energy availability.”

But do you need a CGM to realise you need to eat more? I don’t think so.

Unless disordered eating has skewed your self-perception, more obvious and cheaper indicators include fast weight loss, fatigue, low mood and poor-quality sleep.

Will monitoring blood glucose improve your sleep?

Will Girling, a nutritionist at EF Education-EasyPost, says recording your blood glucose while you’re asleep is “one of the best uses” for CGMs.

If your blood glucose dips into a hypoglycemic event overnight, he adds: “You're probably not having sufficient carbohydrate intake over your whole day.

“So you're not able to maintain blood glucose levels while you're asleep. This may disturb your sleep and make it less restful.”

However, if you turn your phone off overnight, it loses connection with the sensor. You can reconnect them in the morning.

But most sensors can only store eight hours of data. If you sleep longer than that, the data will be missing.

Learn from your mistakes?

While using Supersapiens, the onus was on you to follow the ‘onboarding’ tutorials and conduct experiments on yourself.

Some of these, such as a 90-minute fasted time trial, seemed perverse to me because they could be detrimental to your training.

I didn’t think I could base my cycling nutrition on my blood glucose readings. These are influenced by much more than what you eat, as Supersapiens itself and independent research points out.

Numbers vs intuition

In a data-rich world, feel can be underrated.

I didn’t need a blood glucose graph to tell if I had met the carbohydrate demands of intense rides: if you’re flying with a relatively low rating of perceived exertion, you know there’s plenty of fuel on the fire.

What’s more, in the wrong hands, I think CGMs could be detrimental or even dangerous.

Without sufficient understanding, you might conclude that all blood glucose spikes are bad.

In fact, endurance athletes want blood glucose to rise as a consequence of sufficient carbohydrate intake before and after hard workouts.

Continuous glucose monitoring apps make this clear, but not everyone will grasp it. Fear of blood glucose rises could cause undereating.

What are the alternatives to continuous glucose monitoring?

Supersapiens claimed its technology helped athletes work and meet their fuelling needs. Now Levels is moving into this space, marketing its technology more broadly as a wellness device for health-conscious people.

Metabolic efficiency testing

But McDermott says the best way to determine your carbohydrate requirements is metabolic efficiency testing.

Some university sports departments offer the service for about £110. You perform a ramp test on a stationary bike while wearing a face mask.

McDermott says: “It'll tell you exactly how many grams of carbohydrate or fat you use at any given intensity, ranging from 100 to 340 watts.”

To me, metabolic efficiency testing seems good value. It costs little more than one Supersapiens sensor, which lasts two weeks.

Blood lactate testing

In footage and images from WorldTour training camps, you might see coaches and doctors taking blood samples from their riders’ ears or fingertips.

They’ll probably be measuring blood lactate. This is the cornerstone of the 'Norwegian Training Method', which has brought the country huge success in middle-distance athletics and triathlon.

Lactate doesn’t cause muscles to fatigue (and instead is used for fuel). But its levels in the blood rise in lockstep with metabolic waste products, which do.

As a result, elite athletes use blood lactate testing to calculate their training zones based on the three-zone model. Some sports scientists prefer this to the more popular Coggan model based on Functional Threshold Power.

Coaches also use live blood lactate levels to tweak their athletes’ workouts as they train.

Girling says EF Education-EasyPost measures riders’ lactate while they put in efforts on a climb. They tend to take a blood sample at the top, but can’t record what lactate is doing during the effort, for example.

Continuous lactate monitoring would fill in the gaps, but would still be banned in UCI races.

Sensors galore

CGMs are just one kind of sensor elite cyclists are using to record data to gain a competitive edge.

Several companies claim their aerodynamic sensors measure CdA in real-time on the road.

Some WorldTour teams are taking advantage of the UCI allowing core body temperature monitors in competition.

Meanwhile, we’re told pro teams are also interested in hydration sensors that measure sweat rates.

A price too high

Perhaps the biggest issue with CGMs for non-diabetics is the price.

Instead, you could hire a premium cycling coach or nutritionist. They’d advise you on what to eat rather than you having to guess based on CGM data.

That’s the approach I’d take if I had that much to invest in my performance.

Girling is a nutritionist himself, but he makes a valid point: “Interpretation of the data is important.

“If you're not sure how to interpret it, then it becomes a bit pointless.”

Gone but not forgotten

The demise of Supersapiens doesn’t necessarily spell the end for continuous glucose monitoring.

The popularity of CGMs for wellness is growing and may become the dominant use for the devices among non-diabetics.

Researchers say continuous glucose monitoring is promising for endurance sport, provided certain conditions are met.

Its accuracy during exercise needs to improve. We also need to learn more about the causes and implications of blood glucose fluctuations in endurance athletes at rest.

Whether CGMs catch on in cycling or not, this is certain: to the dismay of the UCI and purists, cyclists will record ever more data in future.