Icelandic manufacturer Lauf intends to produce a leaf-spring rear suspension system to be used on bicycles.

When Lauf launched its unique-looking leaf-sprung bicycle fork, it was well-received by some and laughed at (or perhaps “lauffed at”) by others.

Ground-breaking and unique innovations are often greeted with mixed opinions — and can mostly be taken as a sign that a product is either going to shake things up or simply flop.

Lauf has now been in operation since 2010 (when the company was founded in Iceland by an engineer and an industrial designer), and its forks certainly haven’t disappeared.

They aren’t products that will become completely mainstream, but, for certain applications, they are effective (sometimes less so) and relatively popular in the gravel racing scene.

Lauf has expanded since its beginnings and now sells a range of forks for mountain biking and gravel riding, handlebars and even its own complete gravel bikes. The company remains small, with fewer than 10 staff, but its aspirations are still growing.

Leaf spring bicycle suspension

This leads us to the next chapter in Lauf’s story – one that hasn’t actually been written yet.

The company is now working on a rear suspension system that will provide up to approximately 80mm of travel and will be aimed at gravel bikes. As one would expect from the brand, this system will based on a leaf spring.

As with Lauf’s front suspension forks, the company sees a number of advantages to a leaf spring; it can be lightweight while providing bump absorption for smaller hits; has minimal friction; and it needs very little maintenance.

Plus, Lauf says, there is “low manufacturing complexity” with such a system and the end result provides “pleasing aesthetics”.

Lauf tells us its new system, which is very much in its early days and “a few years… probably” from production, will be ground-breaking for a number of reasons, and there are three patent applications for variations of the idea.

The company claims that its envisaged suspension system will achieve the following: short-travel, tuneable rear suspension with “barely [any] added weight”; it will allow its user to tune to an “exact preferred stiffness”; it will be adjustable “on the fly, maybe at the touch of a button”; and it will remain “completely stiction free… responding to even the smallest of bumps”, all while looking “largely like a ‘traditional’ road bike”.

Plenty of bike manufacturers use and have used different configurations to achieve short-travel suspension for cross-country mountain bikes, road and gravel bikes – Moots’ YBB micro-suspension and Niner’s CVA system offer two different takes on how to soften the ride on a gravel bike.

However, Lauf’s idea is to remove the need for pivots and dampers, and in doing so remove friction, helping to free-up the first millimetres of travel that are oh-so-important in a short-travel system.

All three versions of the idea and their possible variations appear to rely on flexible chainstays.

On the other hand, the patent applications do leave open the possibility for a pivot to be included at the junction between seatstay and leaf spring and the potential for “elastomer materials” and other forms of basic damper to be inserted in order to tune the action of the spring.

The three patent applications

The patent applications, titled “A rear wheel suspension system for a bike” and “A low travel rear wheel suspension system for a bike”, cover three ways in which the system might be made.

They also detail what Lauf sees as problems with currently-available rear suspension systems, and how its alternative is going to solve them.

All three patent applications are largely similar.

They break down current suspension systems into three categories: four-bar linkage, single pivot and “flexible chainstays and seatstays combined with a telescopic suspension unit, without supplemental means of guiding its telescopic suspension units”.

While the merits of a spring-and-damper system with linkages and pivots are noted, the issues at hand, as Lauf sees them, are the complexity, weight, maintenance and friction that its leaf spring system might avoid.

Technology A describes the system in patent application 22173EP01, with a number of variations on the same theme and “up to approximately 40mm” of suspension travel. In this configuration, Lauf’s idea is to create a leaf spring using a cavity in the seat tube, thus creating a flexible area that the seat stays attach to.

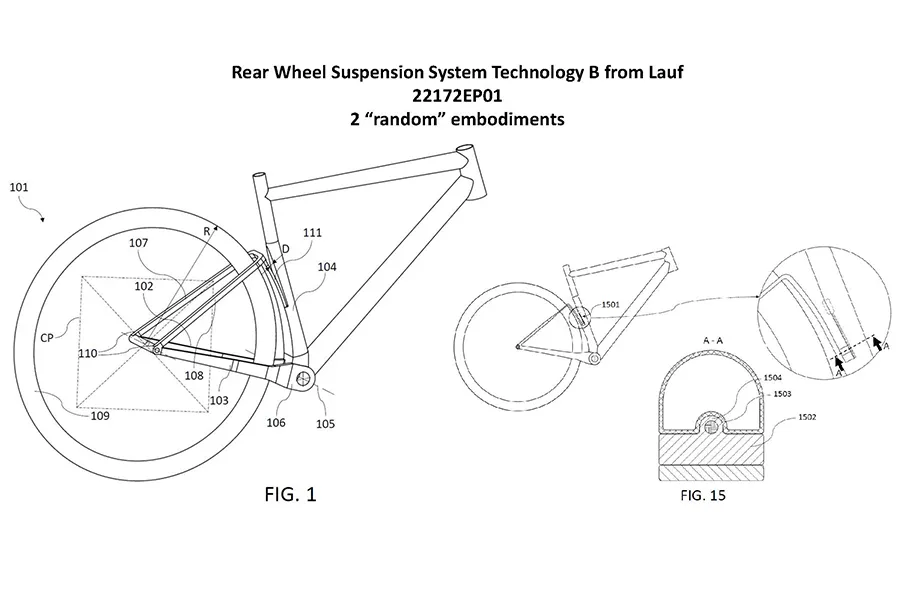

Technology B, patent application 22172EP01, details what is probably the easiest system to understand visually. This version is for “up to approx. 80mm of rear wheel suspension”, with a curved leaf spring built into the seat tube that attaches to the seatstays.

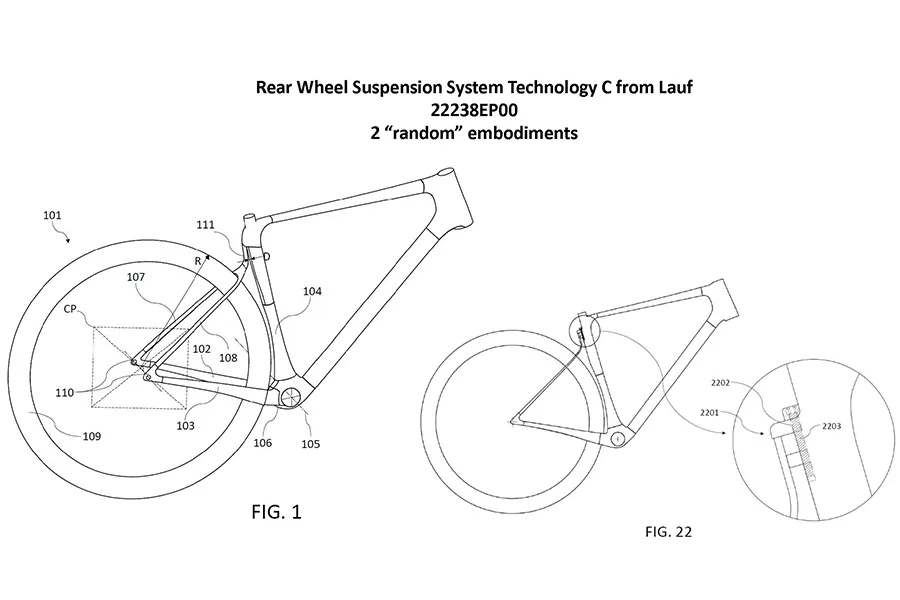

Technology C, patent application 22238EP00, is also aimed at providing up to 80mm of travel (although, from Lauf’s correspondence with BikeRadar, it seems unlikely they will aim for this much travel from either Technology B or C). In this version, the spring is almost perpendicular to the seat tube.

The three patent applications go on to describe the various ways in which Lauf might realise its simple (but hopefully effective) suspension layout, as well as the mechanical, hydraulic, and electric ways in which the suspension stiffness might be adjusted on the fly.

With a number of distinctions in each system and plenty of scope for alterations, they make a good read — if you have plenty of time on your hands.