Earlier this year, the two big players in mountain bike suspension released brand new forks: the RockShox Zeb and Fox 38.

Both have massive 38mm upper tubes, making them even stiffer than their already capable siblings, the Fox 36 and RockShox Lyrik. They're both aimed at long-travel enduro bikes and are designed to excel in the most challenging terrain.

To find out which is best, I’ve been back-to-back testing top-tier versions of these forks over the last few months, using Motion Instruments suspension sensors to add more insight. Before I get into how they perform on the trail, let's look at the technology that's gone into them and how they stack up on paper.

Fox 38 and RockShox Zeb travel options

Fox offers the 38 with 160mm to 180mm travel, while the 2021 Fox 36 is confined to 150mm and 160mm travel options.

Unless you want a 160mm fork, you don’t have a choice between the two options in Fox's range. There's more overlap in the RockShox range.

The Zeb is available with 150mm to 190mm travel, and RockShox still offers the Lyrik with 140mm to 180mm travel, so most customers can choose between the Lyrik and Zeb depending on how much they value stiffness and weight.

Both forks require a swap to a separate air shaft to change the travel. Zeb air shafts cost £42 and for the Fox 38, they cost £99.95 in the UK.

Rockshox Zeb vs Fox 38 weight – which is lighter?

The Zeb weighs 2,297g, while the 38 is 66g heavier, at 2,363g.

Those figures are measured on my scales, with uncut steerers and in 29in x 170mm configurations.

Roughly speaking, the Zeb and 38 are both about 250g heavier than the equivalent Lyrik or 36, respectively.

It's also worth mentioning the Zeb has a 200mm brake mount and the 38 a 180mm. While the 38 retains the option to run a smaller disc (though I doubt many people will use that option), the Zeb saves a further 24g or so over the 38 when using a 200m rotor because there's no need for a 20mm post mount adaptor and the correspondingly longer bolts.

Rockshox Zeb vs Fox 38 stiffness – which is stiffer?

Fox claims the 38 is 31 per cent stiffer laterally, 38 per cent stiffer torsionally (steering stiffness) and 17 per cent stiffer fore/aft than the 2021 Fox 36.

Meanwhile, the Zeb is claimed to be 7 per cent stiffer laterally, 21 per stiffer torsionally and, interestingly, only 2 per cent stiffer fore-aft when compared to the Lyrik.

That last figure is a surprise given the fore-aft flutter when smashing into rocks or braking hard is (in my experience) the main direction you’re likely to notice a fork flexing.

I asked RockShox why it didn’t make it stiffer and the brand told me it didn’t necessarily want it much stiffer than a Lyrik in case it was detrimental to comfort. But it admitted it hadn’t tested any prototypes that were stiffer than the production fork.

While there is speculation that a fork can be too stiff, and that fore-aft flex can reduce harshness on certain bump shapes, I’m not convinced. I’ve never thought a flexier fork, such as a RockShox Pike ever feels better than a Lyrik, for example.

Similarly, I’ve never felt that a stiffer fork, like the dual-crown Boxxer downhill fork ever performs worse. I suspect that given most of the fore-aft flex occurs in the crown of a single crown fork, RockShox was simply unable to increase stiffness in this area without increasing weight or cost too much.

The 38's steerer is internally ovalised, so there's more material at the front and rear of the tube. Perhaps this explains how Fox was able to boost fore-aft stiffness by such a margin over the 36.

If you're wondering why both forks use 15mm, rather than 20mm, axles, it's because 20mm axles don't necessarily make for a stiffer fork. It's the enormous clamping force the axle provides (equivalent to about 5 metric tons), pressing the legs against the hub, that provides stiffness to the system.

Much like spokes in a wheel, the bending stiffness of the axle itself is largely irrelevant. RockShox apparently considered using a 15mm axle on the latest Boxxer downhill fork, but went with 20mm because it's thought to be stiffer.

Fork tech

You can find out more about the design details of the Fox 38 and RockShox Zeb in our original news stories, but in this review, I’ll run through the most interesting technology and features that differentiate these forks, along with a little on how that influences setup.

Starting with the Zeb, it uses a Charger 2.1 RC2 damper, much like you’d find in a Lyrik, with low-speed and high-speed compression damping, plus low-speed rebound damping adjustment.

The air spring piston seals against the full width of the stanchion tube, and that wide piston area means correspondingly lower air pressures. I’m running just 66psi in this 170mm-travel fork.

The positive volume is greater than a Lyrik, so it’s easier to use full travel especially in the longer travel options (the longer travel Lyriks are hard to use full-travel unless you set them up quite soft in their beginning-mid stroke).

Despite that, I’ve swapped between one and zero spacers in this 170mm fork, depending on the terrain, without bottoming out.

Just like the updated 2021 Lyrik air spring, the Zeb's air piston passes its transfer port right at the start of the travel, at top out.

That means you don’t need to cycle the fork to equalise the pressure between the two chambers, and then re-set the air pressure, after inflating the spring, so set up is easier. But in the case of the Zeb, it compromises beginning-stroke sensitivity a little.

The Fox 38 uses a floating axle design. Due to the bike industry’s unique approach to quality control, not all 110mm hubs measure 110mm-wide exactly, and perfect alignment is critical for minimising friction in a fork.

In this design, the axle clamps the hub against the left leg with a stepped collar, then the right leg can self-align before clamping onto the axle with a pinch bolt. In theory, this allows the legs to be perfectly parallel, independently of the hub width. It takes a little time to do properly, but according to Fox it can cut friction significantly.

There is a quick-release version, which needs to be set up once per wheelset and then works like a regular quick-release axle until you swap wheels.

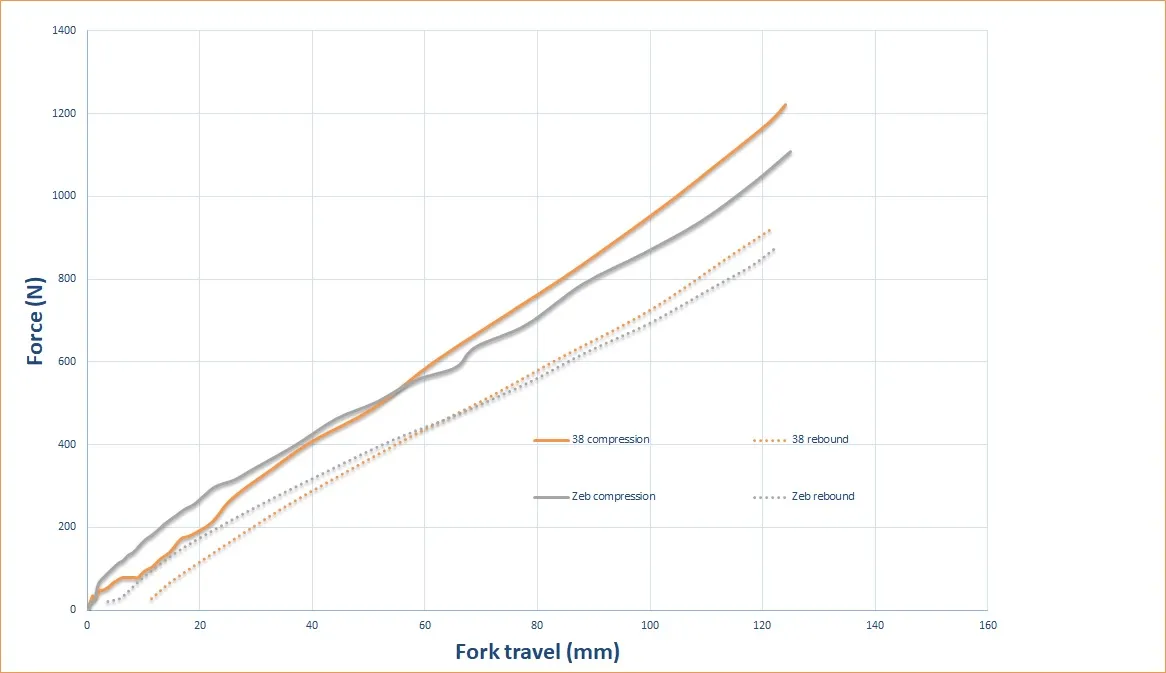

Measuring the spring curves

I arrived at these settings through trial and error on the trail. I then tested both forks with these settings on a spring dyno, which measures force against travel distance (thanks to Mojo Rising for letting me use its equipment).

Fox 38 and RockShox Zeb fork setup

Compression wise, I've been riding with both forks fully open for testing over fast, rough tracks because I find that more compression damping gives me sore joints in my fingers and causes the front wheel to catch on fast square edge hits.

I want the fork to move out the way freely and I don't find the lack of compression damping reduces support too much.

With the Zeb, adding low-speed compression helps hold it up under braking for steeper terrain, but compromises sensitivity. On the 38, I’m usually happy with it fully open, even on steep tracks, but I've run it anywhere up to fully closed on both adjusters on very short, steep and slow trails.

I don’t imagine many people will need it firmer than that, but be aware due to the narrow compression range, the adjusters don't make a noticeable difference unless you wind on several clicks at a time.

Want to learn more about suspension setup?

Seb is our in-house suspension expert. He knows more than most about how to set up a bike's suspension, and his in-depth guide on how to set up suspension on a mountain bike is a great place to get started if you're new to the sport.

On rebound, I like the fork to return as fast as possible before it starts bouncing and skipping off the trail. This helps it to ride higher through rough terrain when paired with the light compression damping. I have the Zeb ten clicks from closed (out of eighteen), which is about as fast as I can have it before it becomes too lively – it actually tops-out if set any faster than this, due to that higher spring force near the start of the stroke.

Meanwhile, I have the Fox 38 just one to two clicks from closed on high-speed rebound, but fourteen clicks out (almost fully open) on the low-speed rebound. That makes it very fast and responsive over small bumps, but when hitting something hard, it doesn’t spring back too fast from deep in the stroke. I’m not sure if this is the best setting but it feels pretty good to me.

The Motion Instruments data tells me that the 38 is rebounding faster on average, but the fastest rebound speeds are with the Zeb, which makes sense given the firm high-speed damping on the 38.

I’m completely happy with how the Zeb’s rebound is set up, just using the low-speed adjuster, but I think it’s fun to experiment with the independent high- and low-speed rebound on the 38, and with even more time to dial it in it could be an advantage, particularly for riders at extremes of the weight spectrum.

The two rebound adjusters do add complexity, but you can simply use the high-speed setting Fox suggests, then experiment with low-speed like normal. However, the recommended low-speed rebound setting is too slow for my taste, so I’d open it up from there.

I’ve also been experimenting with using the 38's bleed valves to create a vacuum in the lowers, by pressing them with the fork partially compressed. This sucks the fork a few millimetres further into its travel and makes the beginning stroke even softer. This robs a little of the travel because the fork can’t extend fully, but for flat, rooty trails I’ve been enjoying this setup. For the comparative testing, I used the bleeders with the fork fully extended.

Riding the Fox 38 and RockShox Zeb

The spring curve is the main difference you can feel between the two forks in my mind. The 38 sags slightly under bike weight and is noticeably softer in its initial travel. But after that crossover point (somewhere around 50mm in my case) the 38 is firmer.

What this means in terms of ride feel is that the 38 feels more stuck down onto the trail. The 38 spends less time at or near the very top of its travel, so it’s got further to extend into holes or steps, so the wheel is more connected to the trail and it tracks the ground better, offering more grip and a more secure feel.

This was noticeable on rough, fast sections of track when off the brakes.

In these situations, forks can spend a surprising amount of their time in the first part of their travel. This was revealed by the Motion Instruments suspension telemetry – on one rough but fairly flat test track, the Zeb spent 14 per cent of its time in the first 10mm of its travel, compared to 11 per cent for the 38.

Subjectively, and before looking at the data, I also felt the Zeb was a little more abrupt on first touch with some bumps when starting from the very beginning of the stroke, and was more prone to running out of rebound travel and skipping off the trail than the 38, even with the rebound slower.

Also, at the time of testing, the 38 had a lot more ride time on it than the Zeb because I've had it for longer. After testing, I serviced it and the increase in performance was significant. It's now noticeably more active and supple, and I'm using more travel with the same settings.

Due to local lockdowns, I haven't been able to recreate these tests with both forks freshly serviced, but I wouldn't be surprised if the 38 transmitted less vibration than the Zeb under these conditions.

The bottom line – Fox 38 vs RockShox Zeb – which is better?

While the 38 is a clear winner in this test, I don't think the Zeb is a bad fork, but rather the 38 is pretty special.

It has masses of traction and suppleness, with plenty of support which builds predictably without making it impossible to use all of the travel. It offers a great balance of grip, predictability and comfort that allows me to ride faster and with more confidence.

Money-no-object, I’d take the Fox 38. It’s the best-performing single crown fork I’ve tested so far.

But the RockShox Zeb Ultimate retails for £969 in the UK, while the Fox 38 Factory costs an eye-watering £1,300.

So in the real world, which would I buy?

If cash was a concern I’d definitely consider a RockShox Lyrik. I think the Lyrik is noticeably suppler at the start of the stroke than the Zeb. It's also a fair bit lighter and, according to RockShox, not much flexier. You can buy a 2020 Lyrik (which I think has a slightly better air spring than the 2021 fork) relatively cheap online too.

So, do we even need these beefed-up single-crown forks? When riding both the Zeb and the 38, there have been times where I’ve slammed into a catch berm and thought the steering feels very direct. But this could easily just be placebo.

I wasn't aware of either fork flexing much, but rarely do I notice a Lyrik or 36 bending in a distracting way (even though they do flex visibly when riding).

But equally, with the 38, in particular, I didn't notice any harshness due to the stiff chassis or the greater surface area of the large-diameter stanchions. In fact, the comfort, grip and suppleness were all particularly impressive.

The Zeb and the Lyrik have quite different air spring curves, making them hard to compare. I haven't yet tested the 2021 Fox 36, but a comparison between it and the 38 is already in the works.