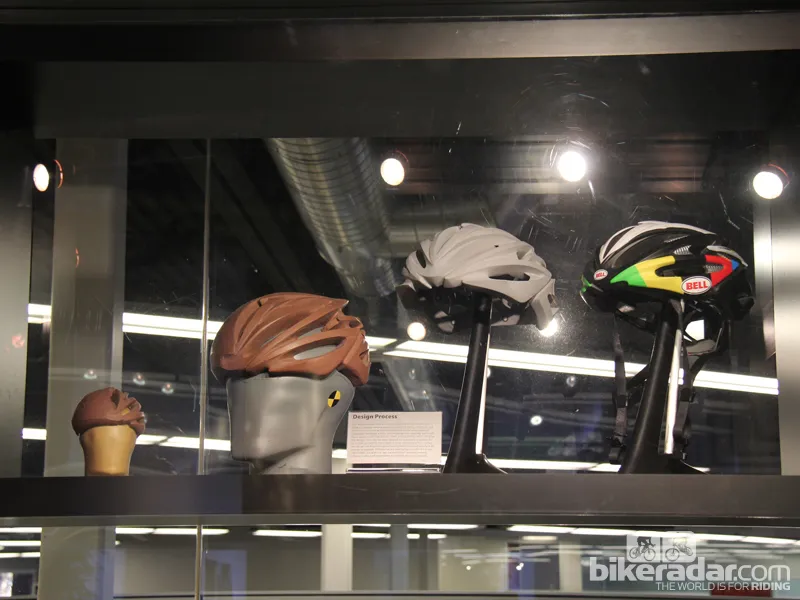

At the beginning, Jim Gentes packed a crude, handcarved model of a cycling helmet into a brown paper bag and took it to a tradeshow to drum up some interest. Today, Giro Sports Design is part of the Easton-Bell Sports empire, and its new research, design and development facility — dubbed The Dome — buzzes with dozens of engineers, graphic designers and lab techs as the company pushes the envelope for helmets across a variety of sports.

BikeRadar visited The Dome in Scotts Valley, just uphill and inland from Santa Cruz, California, a surf town whose culture helps propel and inspire the work inside Giro.

Inside Easton-Bell, helmets are made for cycling, American football, baseball, lacrosse and snowsports.

"We have all these different applications, technologies, designs and materials that can cross-pollinate," said Eric Richter, Giro's cycling senior brand manager.

Half-sized prototypes, called 'eggs', are used to create and test shapes

Some technologies don't carry over, such as the Vinyl Nitrile material used in football and some snowsport helmets. Unlike EPS, the expanded foam material used in cycling helmets that cracks after one crash, VN bounces back to shape — a necessary trait for high-contact sports. So why not use it for cycling, where a crash means throwing out an expensive helmet? "VN doesn't perform well in extreme heat," said Rob Wessen, Giro's director of helmet technology. One US CPSC standard requires structural stability at a wide range of temperatures, and VN "gets squishy" at about 125 degrees Fahrenheit. Also it's heavier than foam.

Easton-Bell doesn't makes helmets in The Dome, but both the design and engineering elements incorporate digital and physical work. On the design front, everything is hand-drawn. Some is hand-sketched and scanned, but much of the work is drawn using a gridded, 3D mold.

Designers use sculpted pieces like this to 'draw on' digitally, capturing the output like a computer would from a mouse

Giro lead designer Eli Atkins said the design team benefits from being part of Easton-Bell, working with the Easton equipment team on color schemes for upcoming model years, for example.

"It's a cultural thing, and it extends beyond this building," Atkins said. "Sometimes we call friends at bike companies and ask what colors they're using."

Once a graphic is created for a particular helmet, it's transferred to the shell material then heated until it begins to droop. Then a vacuum sucks the shell into the mold, where it is formed with the EPS material. Suffice it to say, it's a more complicated process than applying stickers.

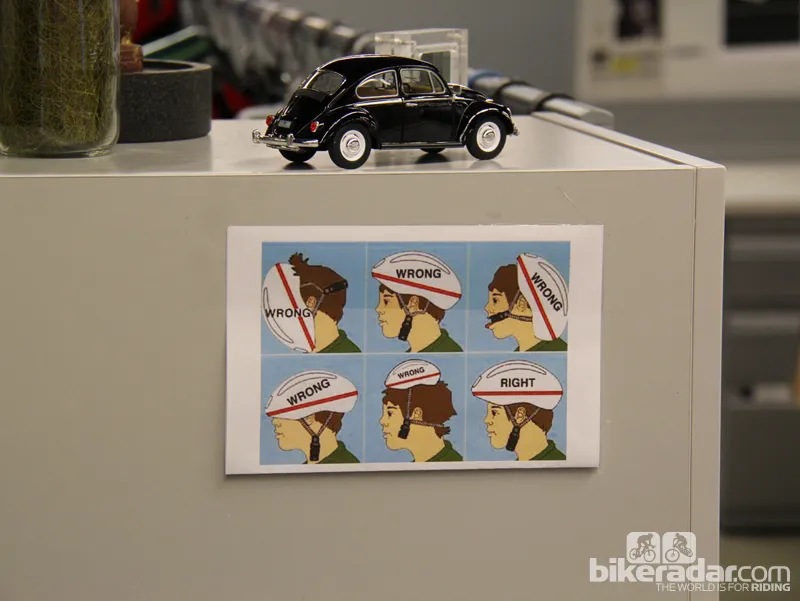

Like any company that sells helmets in the US and Europe, Giro must ensure that its helmets meet all the differing safety requirements. Wessen said Europe's CE standard are somewhat 'easier', as the limits are a little lower for some measurements. For example, the CPSC drop test requires a two-meter drop at 6.2 meters per second. The CE test specifies a lower height and velocity.

A 2m drop test, landing on this metal post, is one of many standard tests

With the Air Attack, Giro's new aero road helmet, the company tested cooling with the reduced venting as well as the aerodynamics. Giro capitalized on the front of the helmet being a high pressure area, setting the forehead pad back from the front of the to better channeling the incoming air. "That high-pressure air wants to go somewhere," Wessen said. "We took advantage by giving it a place to go inside, inside of channeling it around the outside of the shell."

Giro engineers used a system they call the 'Thermanator' to test how well different helmets handle heat. By heating a head-shaped fixture to a certain temperature, then blasting it with air in a wind tunnel at a specific temperature, angle and speed, Giro could measure differences in helmet aero flow with internal gauges. The end result, Wessen said, was the Air Attack was one degree Fahrenheit warmer than the Giro Aeon.

Click through the photo gallery at above right for an inside look inside The Dome.