Keith Bontrager is a legend in the bicycle industry. An engineer with a background in moto-cross, he was one of the pioneers of the eighties mountain bike revolution, hand building highly thought out frames and innovative components – originally from his garage. His guiding principle was that light componentry was good, but something that worked was better, and something that combined the two was best.

In the mid-nineties he was bought out by Trek and the Bontrager brand became their in-house high end component, with Keith being very much involved in developing the products that bore his name. During that period, Bontrager wheels and components were part of the bikes that Lance Armstrong rode to seven Tour de France wins.

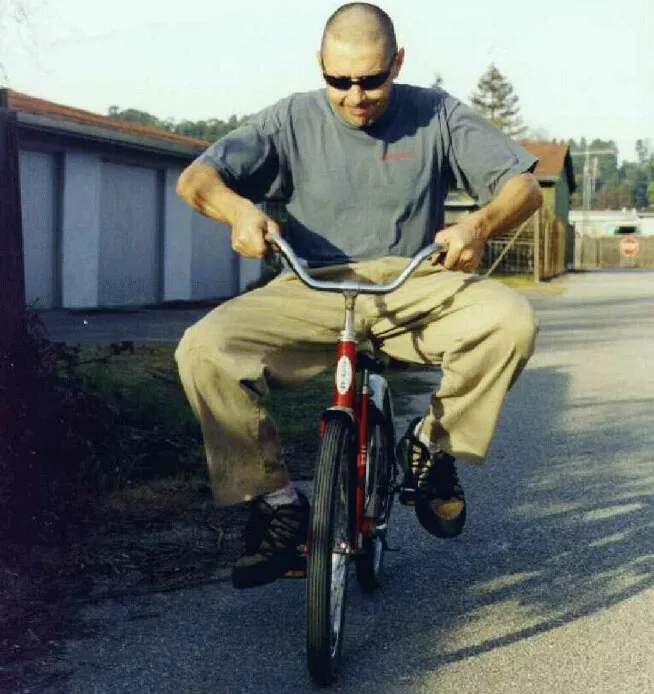

Inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in 1994, he is equally at home crafting components as he is ripping up marathon, twenty four hour, cyclocross and road races around the world.

Bikeradar: You have a long history in designing products for Trek’s high end road bikes. What component of yours do you think has most contributed to their success?

KB: The light carbon wheels. Especially the ones we made for Lance for the Alpe d’Huez TT a few years ago. The rims on those wheels were in the 200 gram range which is damn light. We got them there using the trick lightweight OCLV carbon material Trek used to make the Madone frames lighter. They are fun to ride, surprisingly stiff and solid feeling.

The final test before the Tour started was done by Scott Daubert. He is a pro MTB racer and worked as the Postal team liaison for us when we were testing the wheels. He had a good relationship with Lance too. Scott raced in the Tour of Gila (a US stage race) on the wheels, in every stage. That was enough proof for Lance and he took it from there.

What road team components are you currently working on? And what is your lead time from prototype development to the racers getting to grips with the products?

The development schedule is fairly calm at the moment. The transition from Discovery to Astana wasn’t something we had a lot of time to work out so everything was tentative last fall. That doesn’t mean we are sitting around of course. MTB stuff is getting a lot of attention these days.

We develop parts to help improve the performance of the bikes and parts for pros, and a component that is on the bike of the yellow jersey winner has shown the world that it is pretty good. Of course the team riders have plenty of input in the development process too. But they do not do very much of the actual testing. Pros put a very high priority on finishing races and having bikes that don’t serve up too many surprises. They also want bikes that are easy to maintain. Other than occasional early test rides with one or two team riders to make sure we are on track with a component from the rider’s point of view, everything we give them is very well sorted out before they start using it.

My part is to contribute ideas for new parts or to help others with the projects we are working on. I get to do some ride testing too. I work in Santa Cruz and coordinate with others electronically.

You work a lot with carbon now, has it dramatically improved what you can achieve in the road team bikes’ weight to strength ratio, or is more about ergonomics, or even aesthetics?

Carbon is interesting stuff and has definitely pushed the weight of useable parts much lower than could be done with aluminum or other materials. It’s not without its quirks of course.

Has bicycle design hit its zenith now, or can improvements still be made?

That depends on what you mean. I think the diamond frame road racing bike is fairly close to its limit in the larger engineering sense. There are ways to chase a few more grams out of small parts and some small changes that can be made in rolling efficiency (e.g. bearing materials), but these things are not going to make big differences for most riders. Of course for pros small differences are important.

Changing some of the ancient interface standards like headset and bottom bracket dimensions is making many parts easier to design better. I am not sure where that is going to stop, or if it is. We’ll see.

There are also some changes in transmission designs that are likely. These will make bikes a bit easier in some ways, but more complex in others.

A lot of this is our modern version of a deal with the devil – parts that are easier to use (on the bike) often require big increases in the complexity of the design or assembly. Complex, highly tuned parts are less serviceable - you fix things by replacing them. In that way cycling is like every other manufactured good we deal with.

Off road suspension systems have more than enough travel now, but they can get a lot better. The actual performance of the suspension systems will continue to be refined (i.e. - not all six inch travel bikes are equal). There are quite a few ways this can be done, many very simple, like learning how to tune the shocks on your bike properly. Too many just get bolted on. At the other end are well executed smart shocks - shocks with valves and springs that can be controlled by a microprocessor.

I am a spectator in all of this other than to offer my two cents occasionally.

What’s more important in a mountain bike: speed, efficiency or comfort? Or a combination of all three?

It depends on what the rider wants, but its always the mix that matters. Cross country racers favour the first two, though the trend away from the severe flat bar leaned over positions of the 80s has faded away (as it ought to). Endurance racers, casual trail riders and tourists want a bit more comfort, and will trade a bit of weight for that. They often push things back towards the racer’s blend once they realise that hauling extra metal up a hill isn’t that much fun.

Six inch, five inch, or four inch travel? If you could only have one full suspension bike, how much travel would it have?

For me? 4 inches is fine. I still ride a hardtail often.

You’re still a pretty fast racer, yourself. Any plans to hang up your SPDs, or are you going to keep pushing the young ‘uns at the races? Ever thought of having a vets race series (like they do in tennis) so we can see you take on the likes of Joe Murray and John Tomac?

I haven’t made any plans to stop racing. Is that something one plans? Or is it imposed on you at some point? I think it will be the latter in my case.

I am an engineer who races. Those other guys are racers who do some technical work. I’d give it my best of course, but it would not be a race if we were going head to head. I could probably skin them good if we had to solve a differential equation at the end of each lap. 😉

Tell us about your annual Bontrager UK Twentyfour12 mountain bike race. Any plans to expand them to a series in the UK and abroad?

I have done a lot of twenty four hour racing over the years and Twentyfour12 event is where I get to design my own race. I’ve tried to keep the focus on racing, to make it an event that is not easy but rewarding in the end. That’s the best part of amateur racing, right? I’ve tried very hard to come up with race courses that live up to the traditions we established in the States for this kind of race - they are technically demanding, not easy to just roll around on. It’s challenging and a lot of work but a lot of fun too.

This will be the third year for us and we’ve moved the race to Plymouth. It’s a great spot for a race. After working very hard to build new courses the first two years this venue is going to make laying out the race course much simpler and the results will be much better too.

We’re also putting quite a bit of thought and planning into minimising the environmental consequences of the event. That’s also a tricky one, and very enlightening. I think we are going to accomplish quite a bit in the first year and build on that in the future.

I am not sure where it is going. It would be great to have similar events in other places.

You’ve taken on the Transrockies race and the Three Peaks Cyclo-cross race in the UK. Do you do these events for enjoyment, or for product testing? Or a bit of both?

Both. Things happen in long, hard races. Because of my technical background I can usually explain how it happened and incorporate that into better parts. These races are not easy either, suffering on the race course can be a very good inspiration for new designs.

Your Mud X mountain bike tyres are arguably the best there are for UK winter use. How does a Californian come up with the best tyres for UK riding?

Let me tell you a story.

Put yourself in the mountains of Alberta, Canada on a day when it has been sleeting all day. You are in fourth place in the General Classification and trying hard to catch the racers in front of you (and avoid being caught from behind).

Your hands are so cold you can’t operate the brakes with your fingers – you have to just pull back with your entire hand all at once. You have no real control on the descents. There are scrubby trees growing along the narrow trail and each of them is covered with nearly frozen water so you get a good dose every time you touch them. It’s muddy, but you’ve liked the artful aspects of racing in mud from your motocross days so that is fine, an advantage really. Climbs are a blessing because you can get a little warmer when you are working hard.

Then the sun comes out with 20 km of rolling technical trails to go. Your mood improves, but only briefly.

The sun is drying the mud rapidly, and as it loses water content it turns to clay. The clay sticks to your tyres and clogs your bike, badly, and it stops you. You scrape away the mud every fifty metres with a stick because it’s the only way you can carry on. The bike is too heavy to carry and there is too far to go to do that anyway. You look for puddles to ride through because that helps to keep the mud flowing off the tyres.

If you are a bike tyre designer, this is pretty good inspiration for a mud tyre design, and there is plenty of time to think it over on the way to the finish.

I designed the tyre to solve the troubles I had that day. I wanted a tyre that was narrow to help minimise clogging. I didn’t want the thing to be treacherous on pavement or wet rocks so the knobs weren’t tall and spiky like most mud tyres. I could make it a tubeless tyre so it could be used with sealant at low pressure. That’s where the Mud X came from. I have never used one in California, but it is my favourite tyre in a lot of situations.

You have said that there is nowhere worse for product shredding than Yorkshire. How did you find this out, and do you have a ‘secret’ test centre up there?

I found it out by replacing drive train components too frequently. It would be a very expensive place to test, and most of what you would be proving is in the area of tribology (the science of friction, abrasion and wear) which is not an area of interest for the most part. If I was in the brake or transmission business I would be more interested. As it is I try to ride in the area whenever I can.

Your signature Bontrager frames were highly regarded. Do you miss making your own frames? And any plans to make a few again in the future?

I don’t miss it that much, though I do think about it sometimes. At this point there are no plans.

With this in mind, what do you make of the handmade bicycle market and the resurgence of steel as a great frame material?

Handmade bikes are cool and hopefully will always be around. In a way it is the frenzy for super high performance materials that opened up the handmade steel market again. That’s a fine thing in a lot of ways.

They are not cool because they are technically superior – they aren’t. Once they were the standard, now they are different, so they are back in fashion. There are other reasons to like them - they can be rolling art, or rattle canned black and very practical (you can replace a bent tube). They can be made to fit you in a way that no stock bike does (not everyone needs this but some folks really do), or have all of the little bits in just the right places (like beer bottle openers and other essentials).

A handmade bike is also cool because you know the person who built it, where the thoughts and sweat that went into it came from.

Are you tempted to make anything using Reynolds 953 tubing?

No. I am not a fan of some of the latest and greatest steels. I think they lose the plot in some important ways, but I’ll spare you the detailed explanation.

Any products you’ve seen and thought, wow, I wish i’d come up with that? And who do you most admire in the industry?

There are too many things on bikes that I’d like to have invented to list so I won’t try. There are also quite a few that I am happy not to have, and I’ll leave that list to your imagination too.

There are many people who I should mention – the cycling world is well stocked with admirable people. My personal top admiration award goes to… Ned. He’s a great guy, and after all the things he’s done he is still very humble, down to earth. And I’d be very happy if I was as fast as he is.

What is your carbon footprint like?

It’s bigger than it ought to be, like most Americans, but shrinking.

I ride my bike around town on errands, recycle and compost like a fiend, glean and forage for food, drink tap water and wine and beer made in California, minimise using my car, and consume mostly used things (clothing, books, etc) otherwise. Charity shops here are very well stocked.