Bike fit – it’s something many of us often hear or talk about, but the truth is, few can claim to have it right. In years past, buying a new bike would include a ‘fit’, comprising of a little back-pedalling, a quick adjustment of the saddle height and maybe a tilting of the bars.

Thankfully, those days are long gone. On top of the work of independent bike fitters, we’re now seeing numerous brands market the benefits of bike fit, or their bike fitting systems, claiming the Holy Grail of speed, performance and comfort – all while preventing dreaded injuries.

We recently met with the doctors and experts behind Specialized’s Body Geometry Fit – arguably the industry’s most loudly marketed fitting solution. Specialized may cop plenty of flak on social media – and, when it comes to the bike behemoth's fitting services, some argue they're just another a platform to sell products from.

But whether you're a believer or a critic, the fact remains that few have done more for modern bike fit than the people behind the Body Geometry products. Even if you don't own anything with a Big Red S on it, you're likely to have benefited from their work. Below we talk about some key aspects of bike fit, as well as a few other topical points.

Where it all started

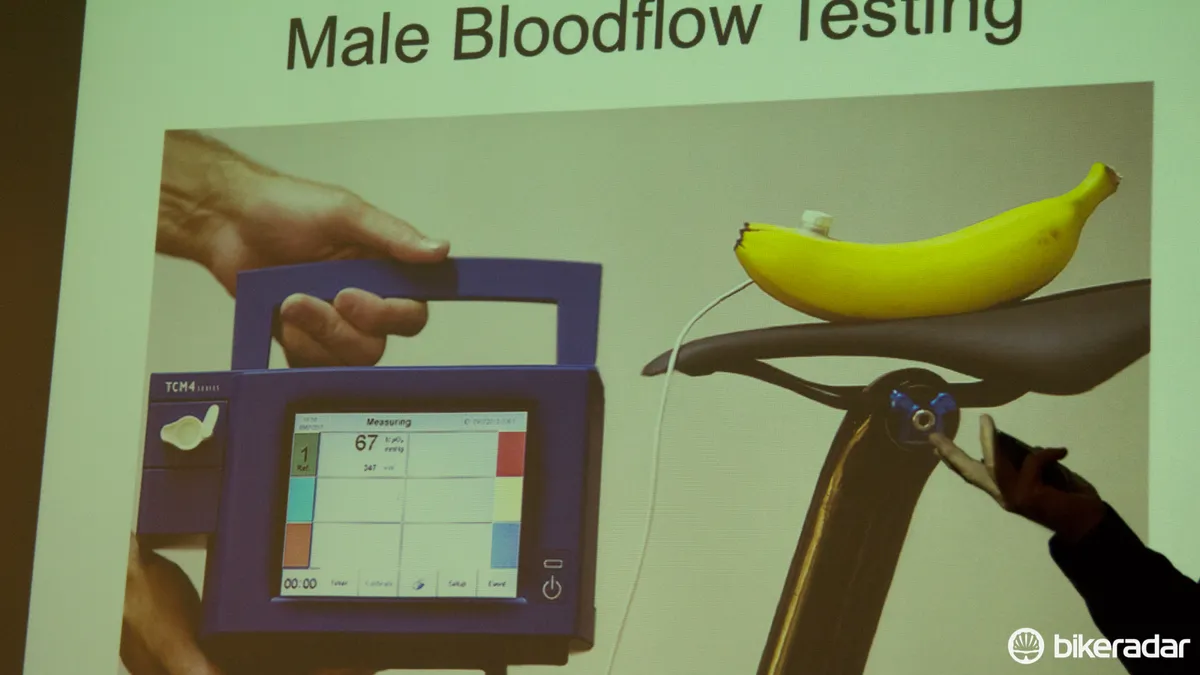

In 1997, the editor of Bicycling Magazine wrote a controversial piece relating saddles to reduced blood flow and erectile dysfunction, which shocked many in the industry. Dr Roger Minkow, an ergonomics specialist who read the article, went to his garage and began carving up saddles, sending the resulting designs to the magazine's editor to check out.

Just two weeks later, a call from Mike Sinyard, Specialized’s founder, set what would become Body Geometry in motion. Specialized's first medically designed saddle, the Romin (Ro- of Roger, -min of Minkow), launched at Interbike 1998 and went on to shift 500,000 units.

Yep, blood flow is one measurement taken during saddle design at Specialized

Following this success, Andy Pruitt (Ed-D) – the founder of the Boulder Centre for Sports Medicine – was asked to join the Specialized Body Geometry team. Pruitt is arguably one of the forefathers of modern bike fitting, bringing a scientific perspective into the field.

Pruitt is also credited with being one of the first people to consider bike fitting from a front-on, as well as side-on approach. It’s from this that he learned just how much correct arch support and foot position affects everything else, paving the way for today’s Body Geometry shoes.

Most recently, Dr Kyle D Bickel, an orthopaedic surgeon who specialises in the hand, joined the Body Geometry team. The recently released Grail glove is Bickel’s first major contribution to the Body Geometry family – and one that apparently took three years of development to reach its market-ready form.

Sizing and fitting

There’s a big misconception in the consumer cycling marketplace, Body Geometry global director Scott Holz told BikeRadar, in that while most people will have been sized for a bike, few will have been fitted.

Scott Holz speaks of the importance of correct foot alignment

“Sizing is anytime you’re taking and applying measurements, while fitting is the customising to the individual need.” Holz said.

Pruitt explained that modern bike fitting systems are merely sizing tools, which only provide for detailed and accurate fits when twinned with the right expertise. Individual components, he continued, can’t possibly make a bike fit well – rather, it’s the set-up and levels of customization to the user

Small factors can make the difference. “Right saddle, wrong place," observed Pruitt, "may as well be the wrong saddle.”

Our bodies are constantly subject to change – perhaps we’ve gained weight, lost flexibility or even been sick. While bike fitting is an expensive exercise, it’s important to keep in mind that while your bike size isn’t likely to change, your bike fit may well do.

“Some pro riders will get refitted five or more times in a single season," Pruitt went on. "Fitting is dynamic, so don’t assume your fit from nine months ago is set and forget.”

Common women’s fit issues

Of course, it's not only men's bodies that can react badly to an ill-fitting steed. Indeed, returning to Body Geometry's starting point – the saddle – women are just as prone to suffering problems associated with reduced blood flow. Minkow reeled off a depressing list of common signs a saddle isn’t working, including numbness, sexual dysfunction, urinary dysfunction and general pain.

“If there’s anything that keeps women off of bikes, it’s ill-fitting, placed or designed saddles,” Holz said.

Differences in anatomy, however, predictably call for different solutions when it comes to female-specific perches.

“Saddle width is the most crucial starting point," Holz continued. "With women’s saddles, there’s been plenty of consideration for women’s anatomy, but not much consideration in offering differing widths. If you can’t support the sit bones in the right place, no amount of cut-outs or channels is going to work.”

The team mentioned that, from their research of sit bones, the spread of sit bone-spacing among both men and women is actually wider than first thought. This is the reasoning behind Specialized adding an extra saddle size to most of its range not so long ago.

Knee and back pain

According to Scott Holz, knee and lower back pain are the most common reasons people get bike fits.

“It’s important to understand where the knee pain is,” he explained. “If the pain is at the direct front of the knee, it’s usually going to be caused by a saddle that’s too low. If it’s the back of the knee, it can be a saddle that’s too high or [can] be caused by what’s happening at the foot."

Holz went on to point out that pain on the side of the knee usually means there’s more to the story, usually relating to a stability issue lower down at the foot.

With lower back pain, meanwhile, it's often said to be caused from a position that’s too long or low. While that's certainly often true, it doesn't tell the whole story.

Holz pointed out a less obvious cause relating to saddle width. “We often see riders on saddles with insufficient width, and they end up rocking on the saddle without a stable base," he said. "Without that stability back there, you’re just toggling on the seat and other muscle groups are being recruited to hold you in place.”

Power meters for fitting

Talking power meters with Pruitt, it’s reassuringly clear he knows his stuff. Pruitt doesn’t believe in looking at wattage numbers as indicators of a successful fit. Instead he uses power meters to allow for reproducible workload instead of perceived effort when taking any form of measurement under motion.

“You can see big influences of power that are instant, but typically real changes only occur once the rider has had a chance to musculoskeletally adapt. You need at least a week of adaptation before you can be sure an adjustment has made a positive (or negative) change to power output,” said Pruitt.

While power may not play a huge part in fitting, vector force, or how the pedalling force is being applied, is big for Pruitt – who was using vector force measurements three decades ago – and will be for many others in the future.

“Of course now you can get off-the-shelf items that measure it," Pruitt said. "It’s a tool – and its all about how you analyze the information. In fit, you want to ensure that ‘Zone 1’ of your pedalling action is optimised for as long as possible. Absolutely there’s a way to use this information and it can be extremely beneficial, but it’s a feature and tool that’s perhaps a little too much for the common consumer. Even in the fit community, probably only a handful of people know how to interpret it.

“I’m thrilled with where the technology is going," he went on. "However, there are too many wannabe experts in the coaching and fitting fields who use this technology [but] don’t have the expertise to really use this information.”

Pruitt added that it could be some time before the potential uses for the data were fully harnessed, concurring with opinions recently offered to us by former pro rider and coach Ben Day.

“Power meters like the Garmin Vector have potential to show so much information – it’s there waiting to be read – but it’s a matter of figuring out what data is useful and what isn’t before offering it,” Pruitt concluded.

Where will the next big innovation be found?

When asked about the next frontier for innovation, all eyes in the room tracked toward Dr Kyle Bickel. It seems the third contact point – the hand – offers a sign of things to come. Bickel believes the key objective is to minimise hand numbness, reduce hand fatigue, and improve control of the bike.

“A glove isn’t the solution to a bad position – much of the work I’ve been doing has arisen from the fact that a bicycle's handlebar is so non-ergonomic," said Bickel.

"Certainly this is the area for most improvement moving forward. It hasn’t changed a whole lot for a couple of hundred years now,” he added.

Notably, according to Pruitt, current handlebars contradict one of Body Geometry's key principles – neutral joint placement.

“[It's about] making the handlebar more ergonomic, and moving away from the traditional drop bar. Marrying 3D imaging and carbon manufacturing will be a natural progression. It’s time for that to happen.” Bickel went on.

But, noted Minkow, achieving that change will mean overcoming challenges relating to ingrained consumer perception. Many people are inherently resistant to breaking with tradition.

“There’s always an inherent business risk associated," he said. "But we’ve done similar things in the past – traditional saddle widths is the same, you have to prove that scientifically there’s a better option.”

As Bickel went on to point out, mountain biking is a whole other story, with so much more variation in bikes’ use and geometry. With this in mind, it seems redesigning MTB bars presents an even trickier challenge than road.

It made for an intriguing end to our discussion – and clearly there’s another exciting chapter for bike fitting waiting to be written.

But given that it took three years to bring the Grail glove to market, we suspect it could be some time before we see something truly new in handlebar design from the Big Red S.