With the spending power of national federations and the narrow focus of such specific conditions, track cycling tech at the Olympic Games is always fascinating to behold.

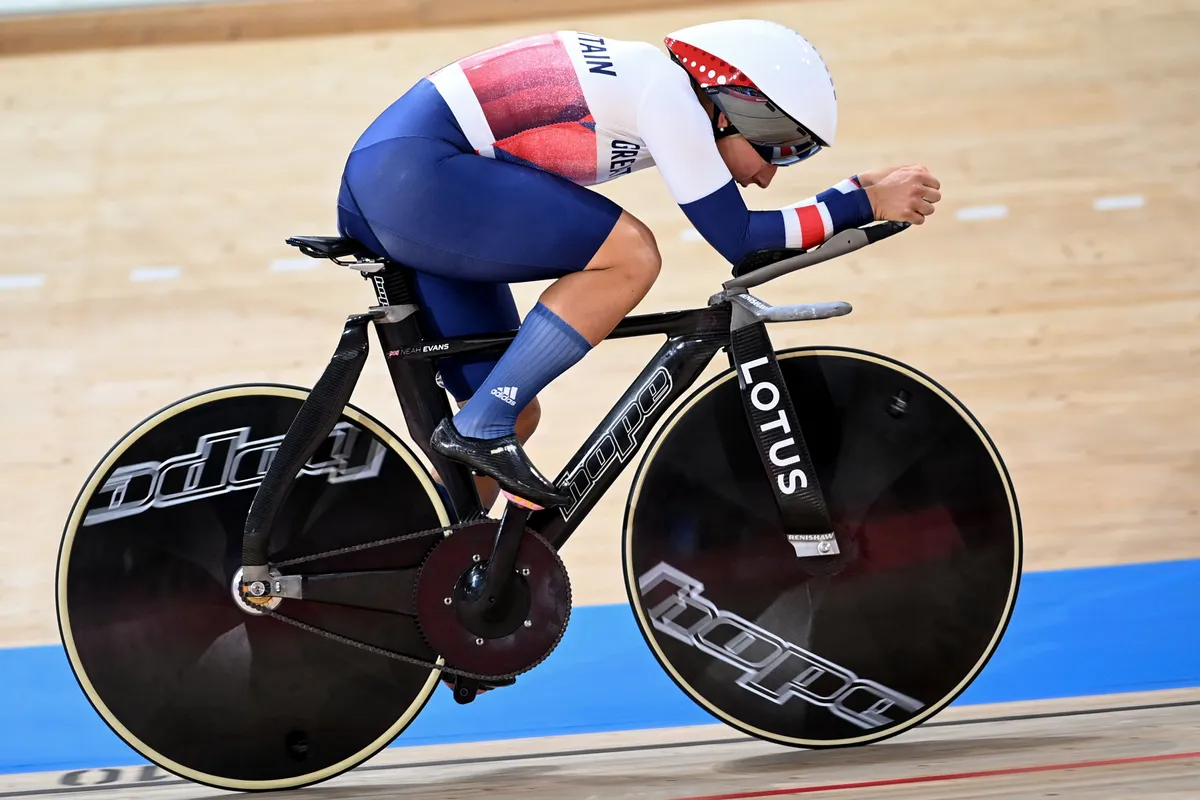

This year’s Games have seen radical and ultra-expensive bikes such as the Hope HB.T and Worx WX-R Vorteq Track, but it’s not all about the bikes.

The tech-heads behind every national team leave no stone unturned in their search for marginal gains, and – as the results have pointed to – Great Britain no longer has a monopoly on optimising tiny details.

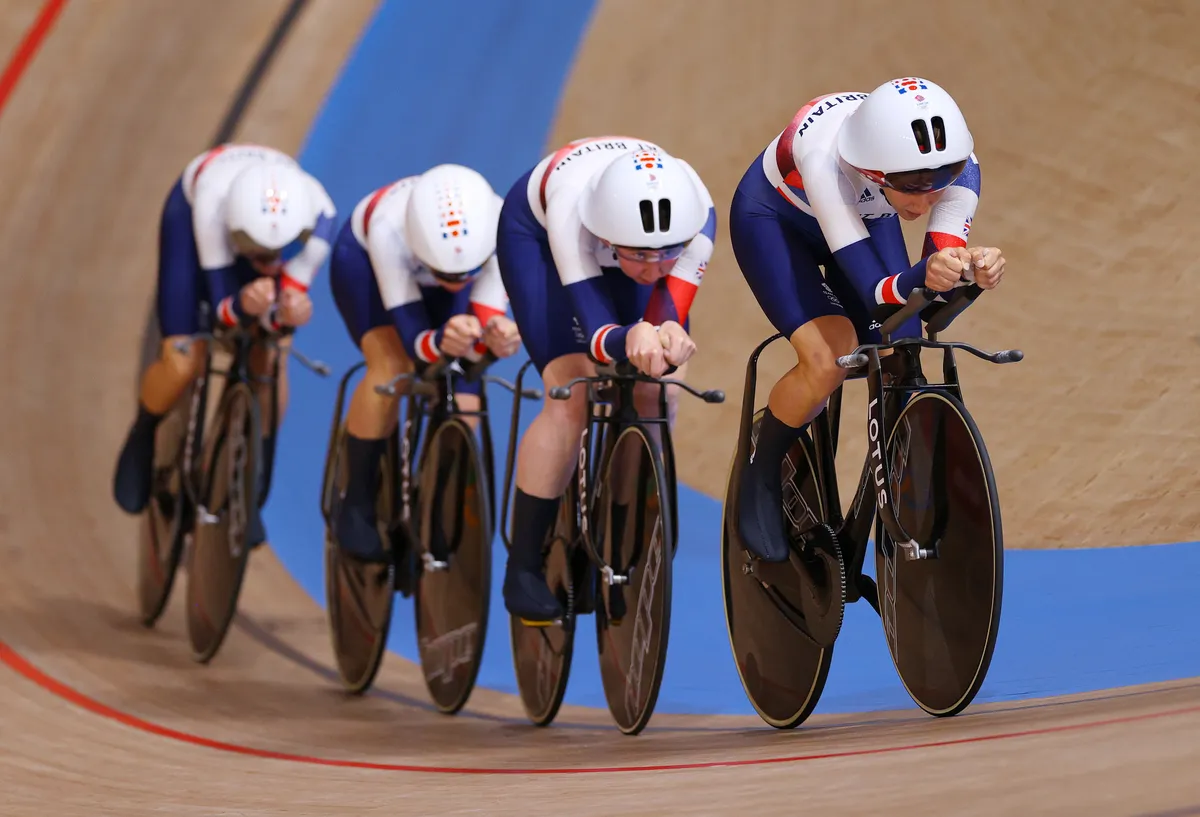

When all is said and done, it’s the athletes who still have to turn the pedals. There’s no denying, however, that when the margins between winning and losing are so small (to cite just one example, the margin of victory in the team pursuit was 0.166 seconds), the tech has the possibility of making a decisive difference.

With that in mind, let’s have a look at some of the track cycling tech stories that caught our eye at the Izu Velodrome.

1. World records tumbling, aero nous rising

As is often the case at the Olympics, track cycling world records have been falling like dominoes.

So what’s going on? Were the old records just no good, or has something changed that’s allowing this generation of athletes to go faster than ever before?

It’s the latter, of course. But it’s not just any one thing that’s changed, as always it’s a number of incremental improvements that add up to big gains overall. It always helps if you can call on riders like Filippo Ganna for your team pursuit squad, too.

To see how quickly things have developed, we only need to look back at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games – things that were once cutting edge already look decidedly outdated.

The focus on aerodynamics has intensified massively in the years since, for example. All of the top nations have invested a huge amount of time (and money) in refining rider positions, skinsuits, framesets, helmets, wheels, components and more.

Engineer and aero expert, Dan Bigham – having not been snapped up by Great Britain – has famously been working with the Danish team.

Having secured a bronze medal at Rio 2016, it won’t have gone unnoticed that the Danes caught the British squad in the first round of heats, on their way to the final round (partly because Denmark’s Frederik Rodenberg Madsen crashed into Charlie Tanfield after making the catch, but also because it was a totally dominant performance). The Danes went on to secure silver behind Italy.

As aerodynamic testing tools have improved and become more accessible, everything is now shaped to be as slippery as possible within the UCI frame design rules.

Previously, expensive wind tunnel testing dominated and was arguably a large barrier to entry for many less well-funded nations, but athletes and teams can now test aerodynamics in the track environment (using tools like the Notio Konect or Garmin’s Track Aero System), gaining cheaper and more relevant data.

As a result, more and more teams are able to make evidence-based improvements to their tech and racing strategies.

Most interestingly for us nerds, not everyone seems to agree on how optimum aerodynamics should be achieved – Great Britain’s Hope HB.T takes a wildly different route to almost every other bike on the track, for example.

It will be fascinating to see if any other federations or brands follow suit going forward. Could wide forks and seatstays become the track equivalent of kammtail tubes and dropped seatstays on road bikes?

With Hope porting the design across to the road in the form of a time-trial bike, surely some enterprising bike engineers will be testing similar designs in the shadows.

2. Drivetrain optimisations

Beyond aerodynamics, drivetrains have been a particular focal point at these games, with nations looking to reduce inefficiencies and improve power transfer to the rear wheel.

This means chainrings have gotten larger, to improve efficiency, and low friction materials such as carbon and titanium are being used to make drivetrain components. All at great expense, naturally.

Great Britain, for example, has reportedly been using chains with a 3/8in pitch, which have a shorter gap between the pins compared to standard 1/8in track chains.

It seems there are two potential reasons behind this: it could allow the use of smaller, lighter and more aerodynamic chainrings while maintaining a similar tooth count and gear ratio; or it could be intended to increase drivetrain efficiency by increasing the tooth count on a similar-sized chainring, which might spread the load more evenly and reduce frictional losses.

Or maybe it’s a combination of the two. Either way, the British team remains unsurprisingly tight-lipped about it.

What’s really spurred all of this development is a burgeoning tech arms race of sorts.

While previously, nations like Great Britain and Australia have tended to dominate track cycling, this Olympic cycle has seen a much more level playing field – teams like Denmark, Italy and New Zealand have caught up and pushed the envelope even further.

3. Shingate and commercial availability

One of the most controversial moments of the 2020 Tokyo Games came in the opening round of the men’s team pursuit when the Danish squad took to the track wearing strips of fabric tape up the centre of their shins (almost certainly for aerodynamic purposes).

Later dubbed #shingate (and subsequently ruled to be against the UCI technical regulations), it showed just how closely every team was looking for grey areas in the rule book.

What went more under the radar was that Great Britain had also complained to UCI officials about the Danish squad’s “undervests” (baselayers), on the grounds they were not commercially available on 1 January 2021.

The rule concerning commercial availability is a key part of the UCI’s technical regulations (the UCI even keeps a record of how much everything registered for use supposedly costs). It’s designed as an attempt to level the playing field and prevent nations from hoarding technology, though whether it achieves this or not is debatable.

Nevertheless, that Great Britain would be the nation to complain about something on these grounds may have raised a few eyebrows, given their history with using UK Sport bikes and equipment (none of which ever seemed to make its way into the hands of their opponents or regular punters – maybe no one ever tried to buy one?).

Though Hope displays prices and purchasing information for the HB.T and its wheels on its website, it’s not clear where one might be able to purchase Great Britain’s skinsuits or overshoes, for example.

Of course, it’s entirely possible all of Great Britain’s kit is actually available to purchase. Maybe you just need to know who to ask (and presumably also have deep pockets).

It’s debatable whether every nation is complying with the spirit of the rule, though, so it’s unusual to see a team complain to UCI officials on these grounds (people who live in glass houses, etc.).

No doubt they’d all say they only have to comply with the letter of the rule.

4. Non-sponsor correct kit

Though many national federations have sponsorship commitments, it’s still common to see nations go against these agreements when it comes to important events like the Olympics.

British riders, for example, could be spotted wearing a variety of different helmets, despite having an agreement in place with Lazer. All have been painted up to look like custom helmets, with all the branding removed, but any tech fan worth their salt should be able to spot the distinctive shapes of each helmet.

At previous Olympics, British cyclists had tended to wear custom aero helmets by Crux Product Design, but at Tokyo it appears each rider may have had the opportunity to use off the peg helmets (Giro’s Aerohead was a common choice).

These were selected to suit their individual riding position and body shape (the effectiveness of different aero helmets is notoriously position and person dependent).

Though it's not clear if Denmark has a sponsorship agreement in place with POC, it's notable that three out of four of the Danish team pursuit squad had abandoned the Swedish brand's often worn Tempor aero helmet in favour of more traditionally-shaped options from Kask and MET (again, with the branding tastefully removed).

Not every team or rider is given such luxury of choice, though.

How much difference does it make? Well obviously no one wants to say, but – just like at the 2021 Tour de France – it’s clearly enough for some well-funded federations to go against sponsor commitments when the most important results are on the line.

5. Narrow bars and bright helmets for bunch racing

As a committed frontal-area-optimisation-enthusiast, it gave me great pleasure to see the proliferation of narrow handlebars across the non-pursuit events. Super-narrow drop handlebars were practically everywhere, in fact.

Presumably, the riders were largely looking for aerodynamic gains, but in congested bunch races like the madison, omnium and keirin, it’s not a stretch to think a narrow bar might make squeezing through tight gaps a bit easier, too.

Track bike specialists Dolan once commissioned AeroCoach to run some tests on 38cm, 33cm and 28cm track handlebars and the resulting aero gains found by switching to the narrower bars were significant – over 47 watts for an endurance athlete moving at 55kph and over 100 watts for a sprinter going 75kph.

Laura Kenny and Katie Archibald of Great Britain, in particular, were using handlebars so narrow there wasn’t much room left between the drops and the super-wide forks of their Hope HB.T bikes.

Kenny and Archibald (and Ethan Hayter and Matt Walls of the Great Britain men’s squad) also had fluorescent yellow aero helmets for the madison, where the pairings won gold and silver respectively.

Fluorescent yellow doesn’t make you any faster (we all know that’s red) but it does make it easier to spot each other among the chaos that is bunch racing on the track.