Despite the proliferation of power meters and their continued refinement over the years, one thing hasn't changed all that much: the price. With few exceptions, nearly all of them cost well over US$1,000 and some much more than that. Some readers regularly question why that is given that many of the embedded components aren't all that expensive.

I posed the issue to several power meter companies. Here's what they had to say.

More than the sum of its parts

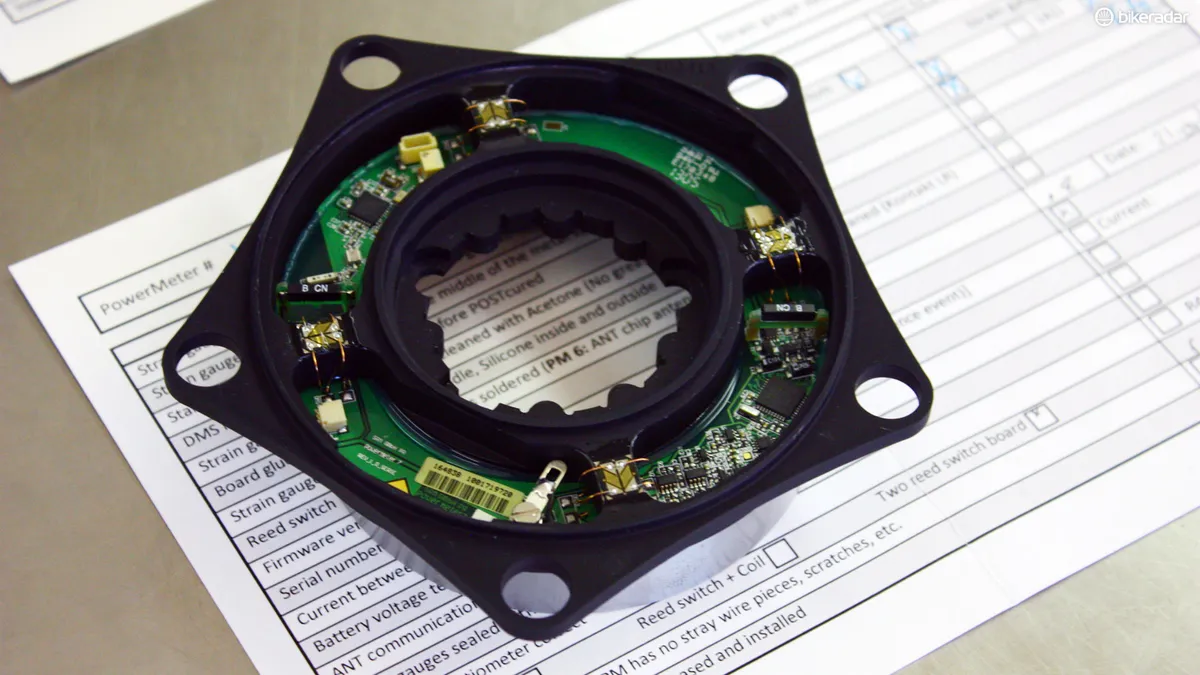

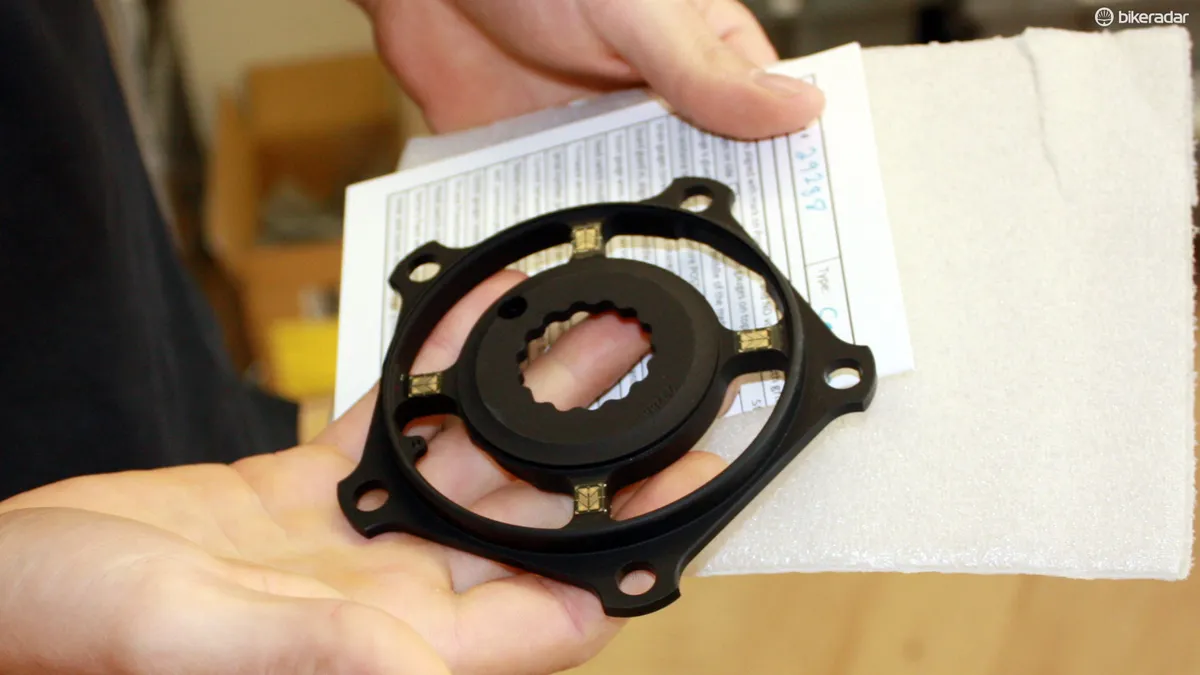

At their essence, power meters comprise a series of strain gauges plus some electronics to receive, process and transmit that information. None of the components themselves are outrageously expensive. However, it's another matter entirely to not only combine all of those pieces so that they generate repeatable and accurate information but to do so without adding much weight or size, and all of that R&D work has to be recouped somehow.

There's a lot involved in making a power meter not only generate a number but the right one - plus it needs to be light, reliable and good looking

"The cost drivers in quality power meters are all of the things around the strain gauges that are required to create a precision instrument within an otherwise interchangeable bicycle component that still offers characteristics that cyclists care about (e.g., light weight, environmental and mechanical robustness, compatibility, etc.)," said Amy Johnson from Garmin. "Tightly specified components (beyond typical cycling industry requirements), premiums for miniaturization, and considerable manufacturing processes (calibration steps, etc.) all add to the cost structure. The cost of strain gauges is not, and likely never has been, the main cost component of a power meter."

Stages Cycling recently shattered the US$1,000 barrier for direct-measurement meters with its Stages Power system, but according to marketing director Matt Pacocha, it'd be tough to go much lower.

"By far the largest source of cost for the Stages Power meter are the man-hours that have gone into developing, engineering, testing and simply assembling the device," he said. "Before Stages Cycling sold a single Stages Power meter, we sank three years into the development of the design and testing it. Day to day, we assemble the Stages Power meter on a true commercial production line [in the United States – Ed.] and it costs to staff these sorts of highly skilled positions. From a raw left crankarm’s unboxing to its repackaging as a Stages Power meter, the device undergoes 16 distinct and separate steps, which take up varying amounts of time over the course of two days. That’s right; it takes two days to make a Stages Power meter."

The Stages Power meter may be small but it isn't easy to get it that way

SRM, on the other hand, stresses the importance of making sure the generated data is accurate.

"The most important aspect of our precision engineered handbuilt products is the constant evolution and upgrade of our products by highly trained individuals in-house at our German, USA, Italian and New Zealand offices," said SRM new product and design manager Jason Simon. "We count on our employees to uphold only the strictest standards, and our obsessive attention to detail at every step is a very meticulous process. There are no shortcuts at SRM because we believe if you're going to provide critical training data that can make or break someone's race (or in some cases, career), you better do it with the utmost accuracy, precision and perfection."

SRM has built its reputation on the accuracy of its power meters. Testing, testing, testing is the name of the game here

More than a number

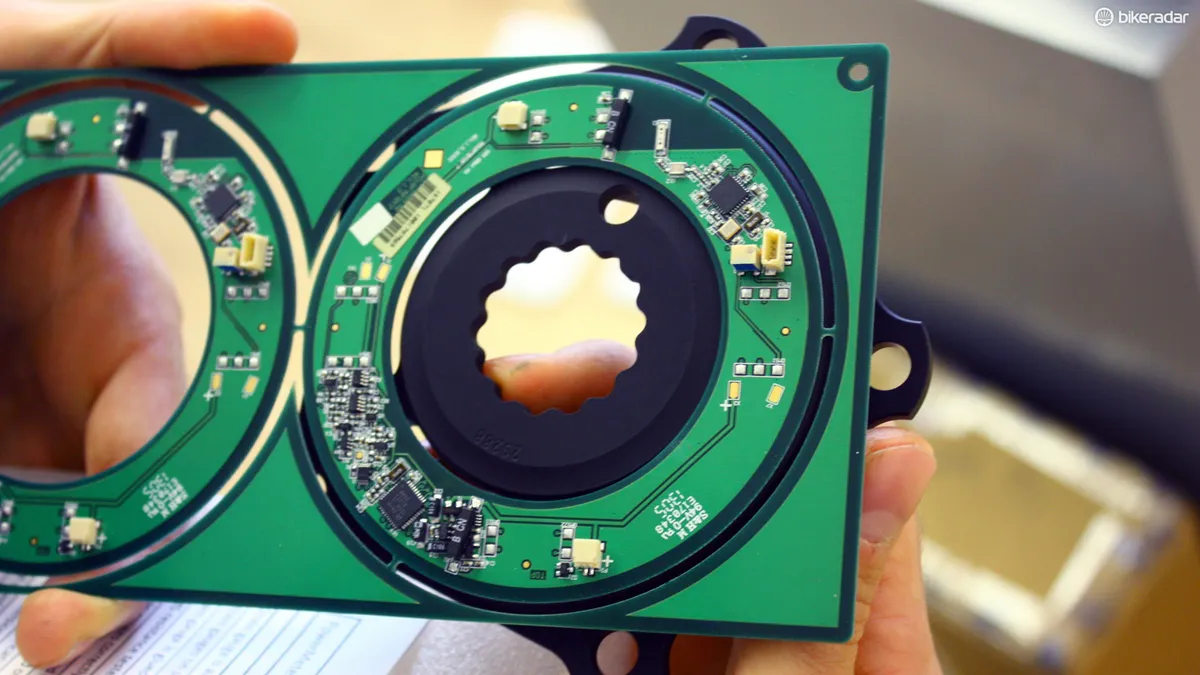

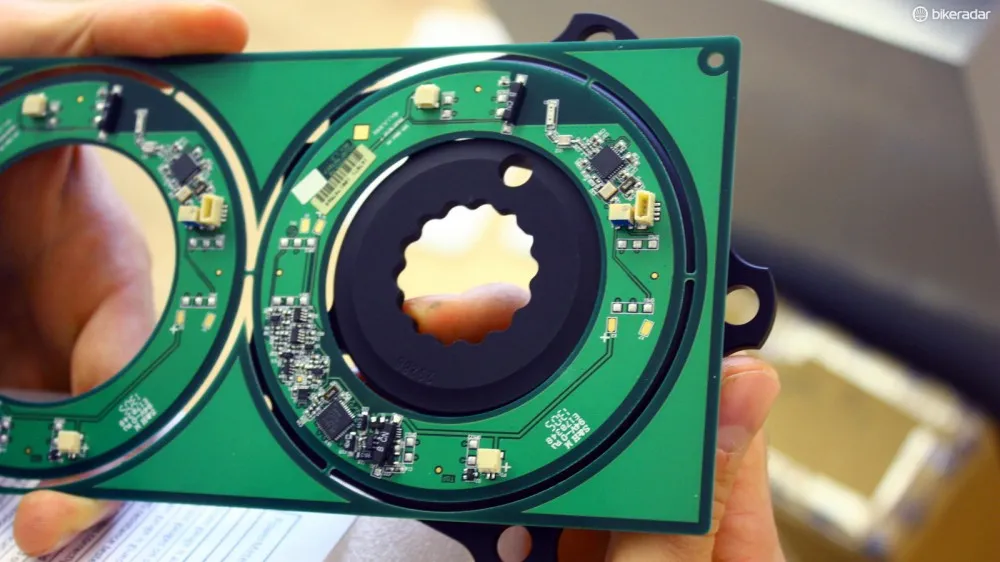

Many meters also offer functionality above and beyond a single power output number. The Rotor and Garmin meters, for example, are actually two power meters in one with dual sets of hardware that provide separate left and right output values. Both also add directional information that can provide further insight on a rider's strengths and weaknesses when properly analyzed.

"When talking about the cost of our power meter, it needs to be emphasized that our product consists of two power meters when others (apart from pedals) are just one," said Rotor power meter head engineer David Martínez. "It is not only about strain gauges, but electronics, radio communication, manual labor, etc."

Are you buying one power meter, or two?

SRM offers its own enhancements, such as higher-resolution wireless transmission that captures more power data per pedal stroke than most systems, plus the possibility of live telemetry to nearby team staff.

Then there's the elegance factor. For example, Powertap's latest GS model packs proven power meter technology into a package that's just 80g heavier than the DT Swiss hub on which it's based. A Stages meter adds just 20g to a standard crankarm while also being virtually invisible. SRM's weight penalty is more on the order of 100-200g but that hasn't stopped countless top professional riders from going that route – and keep in mind that even the Sky team was buying these things themselves last year.

All of those options are also pretty well proven, with generally good reliability, confirmed compatibility and well-established service networks, too.

The parts aren't all that cheap, either

Off-the-shelf strain gauges and associated components may not be all that expensive but if you take the word of these various companies, no one is actually using off-the-shelf stuff. According to these folks, size, weight, performance, and reliability requirements dictate that almost all of these components are custom.

"We use only the best strain gauges and precision German electronics, both of which are custom made to our specifications," said Simon of SRM. "Our latest electronics are among the lowest power consuming ANT+ devices available."

Off-the-shelf components may very well be inexpensive but most companies use custom bits

"Due to dimensional restrictions and other factors such as mechanical stress requirements, we need to develop, test and manufacture specific strain gauges," added Martínez from Rotor. "Every single strain gauge is tested at the supplier's facility before sending, and checked again a couple of times during the different manufacturing steps. Rejection of gauges is high: it is a complex product with complex manufacturing methods, and it is difficult to install so rejection rate for this component is high, which impacts in the cost."

"Electronics are cheap when we talk about millions of cell phones," he continued, "but we are manufacturing specific components in small quantities, and certifying them according to regulations."

Pacocha was even more detailed in his explanation of why Stages meters cost what they do.

"Those in the forums may point out that a strain gauge can cost as little as US$15 but those costs skyrocket when you're talking about a domestically sourced custom strain gauge array, which is what we use. The manufacturer we buy from employs five skilled workers, solely, to assemble gauges for the Stages Power meter – [the gauges] support five jobs alone."

"While we source our printed circuit board abroad, this, too, is a completely custom-made component that houses cutting-edge components," Pacocha continued. "Finally, our housings are made on the Front Range here in Colorado, which again is built to a custom design and affords us the highest quality. Our battery door mold costs upwards of US$20,000 and this is just for a single component; we have a separate mold for each model meter we produce."

Supply and demand

Lastly, there's the age-old law of supply and demand. Because power meters are apparently so labor intensive to produce, no company can easily manufacture the huge quantities that might otherwise help offset the costs. And yet despite what many perceive to be unreasonably high prices, manufacturers are still selling as many power meters as they can make – and sometimes even more – so there's little motivation to make them more accessible.

SRM, for example, apparently posted its best sales numbers ever in 2013.

Even with the incredible price tags, SRM apparently had its best sales year ever in 2013

"I can build a power meter for $100!!!"

Forum posts and article comments are littered with countless people bolding proclaiming that they could easily build their own power meter for a tiny fraction of the cost of buying one ready-made. While that certainly might be possible, doing so while still meeting all of the requirements demanded of a saleable, high-end product is another story entirely.

Are power meter prices higher than they should be? Maybe, but I'd venture to guess that the inflation probably isn't as bad as it's often made out to be.

If you still think you can build your own for a hundred bucks, though, feel free. I'll review it when you're done – and if it's as good as the other stuff out there, I might even buy it from you.

So you think you can do better? Have at it

James Huang has been writing about bicycle tech since 2005 but also has more than 14 years of experience as a shop mechanic. He has worked on every type of bike and enjoys riding most of the them (tri/tt bikes excepted, perhaps). Over the years he's seen plenty of fantastic gear and technology but also a lot of things that just flat-out piss him off. His AngryAsian column tackles both types of tech.