Mountain bikes with hidden shocks are becoming increasingly popular, with brands Scott and Bold leading the charge and rolling out the sleek, futuristic-looking design across most of their mountain bike ranges.

But why is this trend gaining momentum and is it even a good idea?

In this article, we'll explain hidden shocks further, look at how and where the design has been integrated, and weigh up the pros and cons.

What are hidden mountain bike shocks?

Classically, the rear shock of a full-suspension mountain bike is bolted externally to the front triangle's tubes. Different brands use different suspension layouts which, in turn, dictate exactly where the shock is located and how it connects to the front triangle.

Mountain bikes with integrated rear shocks, such as the Bold Unplugged and the Scott Genius, take a slightly different approach to frame design.

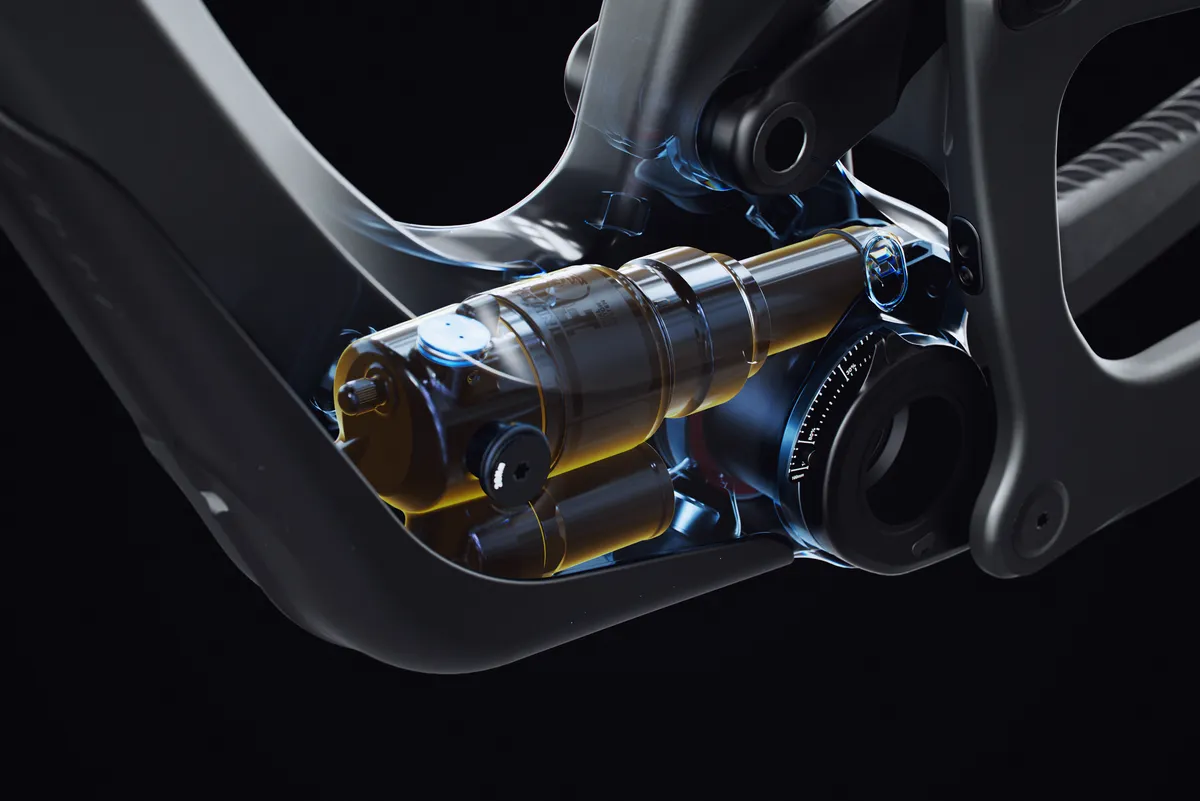

As the name suggests, hidden (or integrated) rear suspension systems are concealed within the bike’s tubes, unlike traditional suspension systems that are visible and located outside the frame, giving the bike a sleek and futuristic appearance.

The rear shock, which is often completely hidden inside the front triangle, is usually located near the bottom bracket area and connected to the swingarm using a linkage.

What are the pros and cons of internal mountain bike shocks?

Pros

The pros of internal mountain bike shocks include:

1. Improved aesthetics: by concealing the shock within the tubes of the frame, designers can create bikes with a sleeker and more streamlined appearance. While the futuristic look might not be everyone’s cup of tea, those who appreciate sleek silhouettes and eye-catching designs will love the latest crop of mountain bikes with integrated rear shocks.

2. Better shock protection: another key benefit of integrating the rear shock is the greatly improved protection from the elements, mud and trail debris it provides. Internal shocks are often completely sealed inside the frame, increasing shock service intervals and reducing wear and tear.

3. Enhanced performance: by sitting within the frame itself, integrated rear shocks can be positioned lower than their visible counterparts, giving the frame a lower centre of gravity. This is often claimed to provide better handling and stability on the descents.

Cons

While the list of pros proves integrated rear shocks open up the potential for improved performance and streamlined aesthetics, internal shocks aren’t without their cons:

1. More complex maintenance: the elaborate design required to house a rear shock inside the frame of a mountain bike adds complexity. Trailside access to the shock is vital, so most brands employ a small hatch in the frame that enables you to adjust your shock on the go. However, this can be fiddly and some designs require more than a standard multi-tool, should you need to remove your shock on the trailside.

2. Limited shock choice: most integrated shocks are designed in close partnership between the bike brand and the suspension manufacturer. This ensures optimal fit and adjustability for a particular frame design. However, it also means that often the frame is exclusive to one model of shock. This limits personalisation.

3. Higher cost: mostly seen on high-end carbon superbikes, such as the £10,999 Bold Unplugged Ultimate, hidden shock technology certainly doesn’t come cheap. Time will tell whether this trend ends up trickling down to less expensive aluminium mountain bikes, but for now, it’s reserved for those with deep pockets.

4. Heat build-up on long descents: due to their location inside the frame, integrated shocks aren’t as well-ventilated. This can cause excess heat to build up on long descents, because the shock isn’t exposed to a cooling airflow. In some extreme instances, this could lead to inferior shock performance.

What types of internal shock designs are there?

Most internal shock designs follow a similar trend. The shock is housed inside the frame near the bottom bracket junction and driven by a set of links, similar to a conventional mountain bike.

Depending on the design of the frame, the shock orientation may be vertical or horizontal. Scott’s integrated offerings, such as the Scott Spark and the Scott Genius, have their shock positioned upright, tucked as close as possible to the seat tube.

Italian manufacturer Berria Bikes uses a very similar layout for its Mako LTD cross-country mountain bike, sharing a strong resemblance to the Spark.

Bold Cycles, which was acquired by Scott in 2019, uses a slightly different approach, positioning the shock horizontally, tucked in around the bottom bracket.

Perhaps the most unusual-looking design is that of the Digit Datum. Hand-built in California, the Datum frame has a custom spring and damper built into its top tube, which is claimed to give it great stiffness, reliability and serviceability.

Another interesting design is that of the Olympia F1-X, another cross-country race bike. The F1-X uses a semi-integrated design, where the air can of the shock is built into the seatpost, but the stanchion protrudes slightly. This design enables the shock to be mounted to the same axle as the chainstays.

Which shocks are used for internal suspension designs?

As we’ve already touched on, most hidden shock frames are designed around a specific rear shock to allow for optimal positioning within the frame.

Scott and Bold both use Fox’s Nude line-up of air shocks for their trail and enduro bikes. These shocks have been designed with input from Scott and can’t be swapped out for other models.

Many cross-country bikes, such as the Scott Spark and Olympia F1-X, use RockShox’s SIDLuxe Ultimate, which lends itself well to integrated designs due to its streamlined shape.

Completely custom bikes such as the Digit Datum employ their own shock design and again, this can’t be changed down the line.

In short, although there are several shock brands and designs employed by different manufacturers for different models, once you have made your choice you are committed to running the stock suspension.

What about coil shocks?

So far, we haven’t seen any coil suspension used on bikes with hidden rear shocks. This could be down to a couple of reasons.

Firstly, coil shocks tend to be much bigger and bulkier than their air-sprung counterparts. This is a big disadvantage, because space inside the frame tubing is limited.

Secondly, coil shocks are also a lot heavier. While we have seen some hidden-shock trail and enduro bikes (such as the Scott Genius and Bold Unplugged), the majority of integrated bikes on the market are designed for cross-country riding. For this use case, a coil shock is simply too heavy and doesn't bring any performance benefits.

If we see the hidden-shock trend continuing to grow, we might expect to see some hard-hitting models with coil shocks emerging. Until then, it’s an air-shock only party.

Will hidden mountain bike shocks catch on?

The future of hidden shocks in mountain biking is still unclear. Seeing an industry giant such as Scott Bikes fully embracing the idea and being well on its way to introducing the concept to its entire MTB line-up speaks volumes about the potential of the design.

However, so far, the rest of the industry has been slow to adopt the trend. The undeniable fact is there’s nothing wrong with conventional suspension layouts.

Sure, the shock is better protected from the elements inside the frame and can be positioned lower, but whether those benefits warrant the extra complexity, cost and reduced personalisation remains to be seen.