If you’ve been paying attention to the pro road-racing scene recently, you may have noticed many riders are increasingly using oversized chainrings.

For a long time, 53-tooth front chainrings were the de facto standard within the professional peloton, typically paired with a 39t inner ring.

As the gears specced on bikes sold to everyday riders get ever smaller, though, pro riders are heading in the opposite direction.

54t or larger chainrings, for example, are now a common sight on WorldTour bikes, even outside of time trials.

Shimano’s flagship Dura-Ace Di2 R9200 groupset moved to offering a 54/40t chainring combination (in place of 53/39t) when it launched in 2021 – and some riders are even pushing into the 60s for certain races.

Are today’s pro riders so fast they simply need bigger gears than before, or could there be more to this tech trend than meets the eye? Let’s investigate.

Pro racers probably are getting faster, but that’s not the whole story

Given the varying conditions, tactics and parcours of professional road races, it’s difficult to make definitive statements about how much faster (if at all) WorldTour racing has become in recent years.

Anecdotally, though, there seems to be a consensus that pro races are increasingly being ridden at faster speeds than ever before.

That each of the previous three editions of Paris-Roubaix – one of the most prestigious single-day races on the professional calendar – have been the fastest yet is hard to ignore, for example.

At face value, the potential reasons behind this perceived increase in speed are myriad.

There’s been the widespread adoption of aero road bikes and related wind-cheating tech, for example. Compare Mathieu van der Poel's Paris-Roubaix bike and kit to that of Fabian Cancellara from 2013, and the difference is stark.

Likewise, more riders than ever are optimising their fitness through the use of power meters in training and racing. There have also been significant advances in reducing the rolling resistance of the best road bike tyres and in our understanding of how carbohydrates affect performance.

Given faster speeds require bigger gear ratios to maintain a rider’s preferred cadence, these advances could therefore be fuelling the adoption of bigger chainrings within the professional peloton.

But what about 10t cogs?

Though increasing the size of your chainrings is one way to get bigger gear ratios, it’s also possible to reduce the size of the cassette cogs.

SRAM and Campagnolo have introduced 10-tooth cogs to their high-end road bike groupsets in recent years for this reason.

Notably, both brands also opted to size down their chainring offerings at the same time.

In place of traditional combinations such as 53/39, 52/36 and 50/34t, SRAM’s latest AXS groupsets offer smaller ones such as 50/37, 48/35 and 46/33t.

Likewise, Campagnolo’s new Super Record Wireless groupset offers 50/34, 48/32 and 45/29t options.

With the 10t cog, riders get top gears equivalent to what they would have previously had with traditional chainring combinations and an 11t sprocket, with the added benefits of lower overall system weight and increased gearing range.

Despite these potential benefits, many professionals riding for teams sponsored by those two brands nevertheless opt for larger chainrings, however.

Given pro cycling has a well-documented obsession with weight, though, why is this?

Bigger chainrings are more efficient

The short answer is that bigger chainrings are, all else being equal, more efficient than smaller ones.

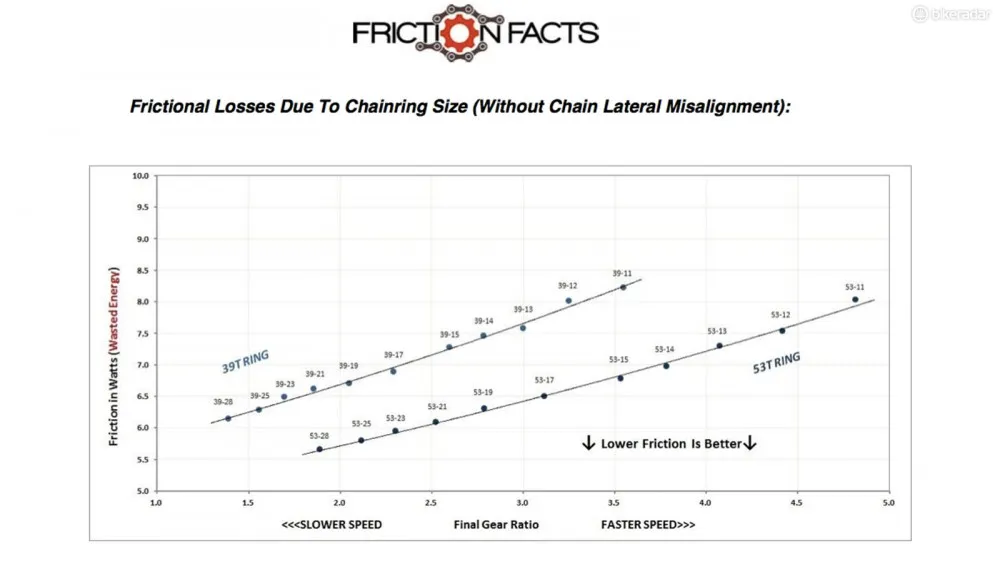

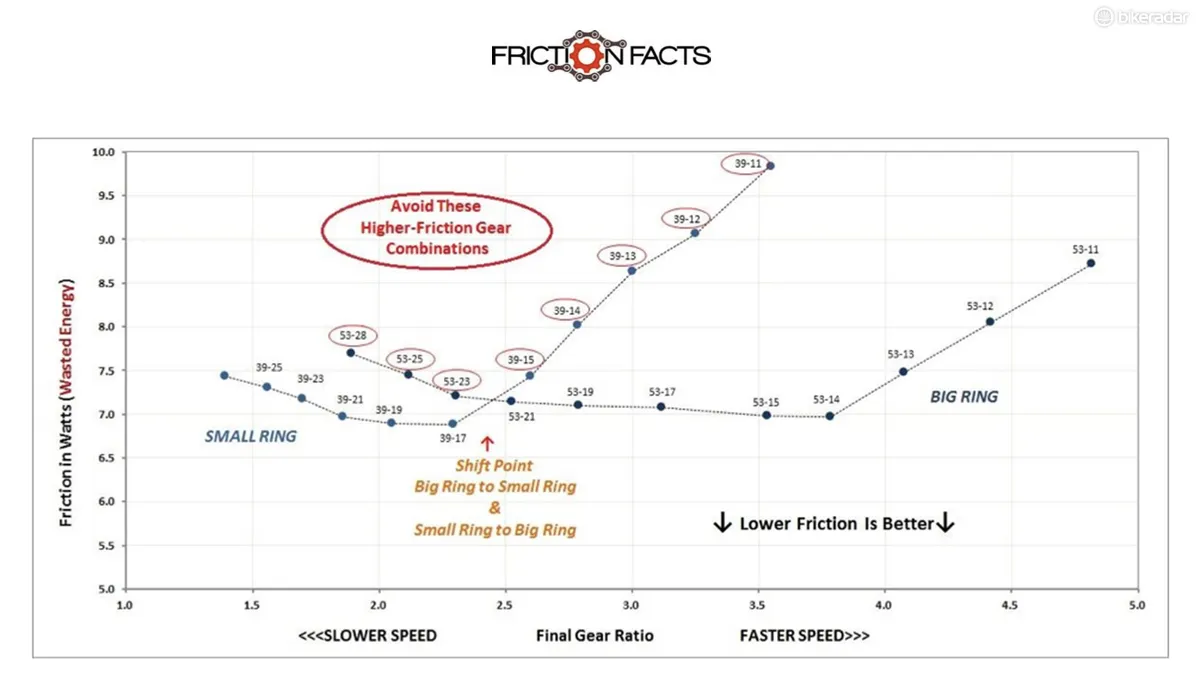

We know this thanks to testing by the likes of Friction Facts – a previously independent company specialising in drivetrain friction testing, now owned by CeramicSpeed.

It found, for example, that a 39x11t gear combination produces around 1.5 watts more friction that a 53x15t combination, despite both combinations offering an almost identical gear ratio.

This is because larger chainrings and cassette cogs elicit lower chain tension and reduce the amount of articulation required at each individual link.

Larger pulley wheels can also be more efficient than smaller ones for the same reason, though the wattage savings from size alone are typically much smaller here.

When accounting for the chainline implications of a real drivetrain, though, the effects of using larger chainrings can be even more significant.

When using a 39x11t gear in a typical 11- or 12-speed drivetrain, the amount of ‘cross-chaining’ can be substantial, leading to increased drivetrain friction.

With the 53x15t combination, though, the chainline will typically be much straighter, and therefore more efficient.

Essentially, pro riders are trying to tap into the efficiency gains of larger chainrings, combined with straighter chainlines.

Four-time time trial world champion, Tony Martin, was a pioneer of this in the modern era, often pairing a large 58t chainring with a wide-ranging cassette during his career.

Nowadays, riders are pushing the boundaries even further.

Tobias Foss of Ineos-Grenadiers, for example, used an enormous 68-tooth chainring for the time trial at the 2024 UAE Tour, while his teammates, Josh Tarling and Ben Turner, used 60 and 62t chainrings at this year’s Paris-Roubaix.

It’s unlikely any of them will have spent much time in their smallest cassette sprockets during these races. However, having a straighter chainline during times of high speed and high power outputs will likely have offered these riders a measurable performance benefit.

Should amateur riders consider using bigger chainrings?

It can be tempting to assume that if the pros are doing something, it must be a good thing.

The best thing most amateur riders can do is optimise our gear ratios for the terrain and type of riding we’re doing, though.

Bigger chainrings and cassette cogs may be more efficient in isolation, but if you end up being over-geared for your rides, your climbing efficiency is likely to suffer significantly.

Likewise, if you opt for a ‘big’ chainring that’s too large, you may spend more time using the less efficient smaller inner chainring instead (assuming you have a 2x drivetrain).

This is likely to negate any performance gain, or even leave you worse off, compared to having a smaller ‘big’ chainring you can use more of the time.

Of course, for certain scenarios, such as flat time trials (which are popular in the UK), it may make sense to run a larger chainring and cassette in search of small efficiency gains.

For general all-round riding, though, it’s best to consider the gearing range you need as a first priority.

In terms of drivetrain longevity, while it's true that the reduced friction offered by bigger chainrings and cassette cogs may extend drivetrain life (again, all else being equal), the best way to reduce wear and tear is to keep your bike clean and use one of the best chain lubes.