It’s every cyclist’s favourite punching bag, but sitting in its Swiss ivory tower, the UCI does set itself up for it.

Whether it’s the 6.8kg lower bike weight limit, which has stayed the same since 2000; proposed gearing limits, which could have the apparently unintended consequence of restricting tyre width; or spats with teams over who gets to bolt a GPS transponder to a rider’s bike, cycling’s governing body seems determined to keep cycle racing in the mid-20th Century.

The UCI’s ‘Clarification Guide Of The UCI Technical Regulation’ is the rule book for equipment used in road, track and cyclocross events. It runs to 78 pages and includes everything – from the number of tubes in the bike frame (Article 1.3.20) to whether you can slot a credit card between the seat tube and the rear tyre (Article 1.3.024).

What’s more, it’s a list that grows every year, and few of the new additions are popular.

Here’s where we reckon cycle racing’s governing body could take the pruning shears to its rulebook.

Handlebar width

From 2026, handlebars used in road and cyclocross competition need to be at least 400mm wide and 380mm between the hoods.

The pushback against this new rule has been enormous.

The UCI doesn’t appear to have considered the impact this will have on smaller riders – particularly those in the women’s pro peloton, for whom narrower bars might be a better, more ergonomic fit.

- Read more: "Blatant disregard" – new UCI handlebar rules ignore the needs of female riders, say experts

In fact, it’s reported that Cervélo warned that 14 riders on the 18-member Visma-Lease a Bike women’s team would need to swap to wider bars to comply.

Speaking to BikeRadar at the time of the announcement, an industry source close to the matter said: “They ignored everything the industry said – literally everything.”

The UCI’s apparent lack of data-led decision-making and reported rejection of recommendations made by experts is baffling.

The 380mm limit appears to have been landed on arbitrarily, and doesn’t even follow the example set elsewhere by the UCI.

Other rules, such as reach on a time trial bike and saddle position, are related to rider height. If the UCI is hell-bent on limiting bar widths, we can’t see why a similar approach couldn’t be applied here.

It’s also a major inconvenience for manufacturers of performance bikes, who have invested in the moulds for narrower, flared carbon one-piece bar/stems that could soon be outlawed.

- Read more: “It’s impossible” – how the UCI’s new controversial handlebar rules will affect pro riders and teams

Gearing restrictions

The UCI has it in for big gears too, because it believes they enable riders to go too fast, risking their safety.

It will trial a limit on gearing to 10.46m of gear development meters (how far a bike travels with a complete revolution of the crank) at a test event later this year.

That limit works out to the equivalent of a 54-tooth chainring paired to an 11-tooth sprocket.

Got a cassette that starts with a 10-tooth cog? Just adjust the derailleur so it can’t be used, says the UCI, cutting riders on SRAM or Campagnolo groupsets down to 11 speeds.

Experts have pooh-poohed the UCI’s proposals before they’ve even been trialled, with the influential head of engineering at Red Bull – Bora – hansgrohe, Dan Bigham, saying “restricting gear ratios simply distracts from making meaningful changes to rider safety”.

Efficacy aside, the subject of gearing development meters is also affected by tyre size, but the UCI has confirmed it will not take into account tyre size at the trial.

This means riders will be able to circumvent the rules by moving to a larger tyre (provided it remains within the UCI’s permitted wheel plus tyre diameter limit – more on that in a moment).

Crank length is also a factor, and the proposed rule would lead to shorter cranks spun at higher cadences to compensate, which would benefit shorter riders.

All of that said, the trend towards larger chainrings is more about drivetrain efficiency than top-end speed – the UCI’s barking up the wrong tree with this one.

6.8kg lower weight limit

Coming from a time when almost all race bikes were far heavier than 6.8kg, the UCI’s weight limit has felt like an anachronism for years.

The swap to disc brakes added mass to bikes for a time, but now top-end disc brake bikes routinely hit, or are below, 6.8kg in weight, without impacting on bikes' rigidity, performance or robustness.

It’s another rule that benefits some riders over others, dependent on their stature, and disproportionately affects female riders.

A 6.8kg bike represents a significantly larger proportion of the weight of a 50kg rider than one who weighs 80kg, so the lighter rider is disadvantaged.

The weight limit is now a constraint on bike development, which is why the lightweight/aero bike has been in the ascendancy.

A lower weight limit, or its removal, would encourage increased differentiation between lightweight and aero bikes – a good thing for bike development and racers alike.

Maximum wheel-plus-tyre size

Tyres are getting wider. But when we asked Glen Leven, Lidl-Trek’s team support manager, if the team would use the latest 40mm-width Pirelli P Zero Race TLR tyre in its 2025 Classics campaign, he was told the circumference would be too large to be UCI-legal.

The spirit of the rule is sound – larger wheels have some advantages, and their use could disadvantage smaller riders who may not be able to use them. This is partly why the UCI has preemptively said it may ban 32in wheels in MTB competition.

Fair enough, but why not just limit the wheel size to 700c?

Riders could then choose whether to ride wider tyres, weighing up their weight and aerodynamic penalty versus their advantages.

Helmet design

The UCI has its eye on your helmet too, proposing rules to limit the use of time trial helmets in road races and set maximum dimensions for TT helmets that would outlaw super-sized helmets such as the Giro Aerohead 2.

It’s not explained how it will differentiate between time trial and road helmets – although early reports suggest this may be based on how the helmet is marketed.

The UCI says this is in the interest of safety, ensuring a rider can hear their surroundings.

But we’ve tested a range of helmets with different degrees of ear coverage and, while a helmet with full ear coverage muffles sound a little, that more comprehensive coverage might prove safer – and isn’t that the spirit of the rule?

In an era where independent testing from the likes of Virginia Tech has arguably pushed forward helmet safety, or at least made it more of a talking point, the UCI could afford to be more daring and specific in this area if its goal is to improve rider safety – and not just to ban tech it doesn’t like the look of.

Sock height

Ah, who can resist the temptation to sock dope and gain an unfair advantage over their fellow riders by pulling their socks up?

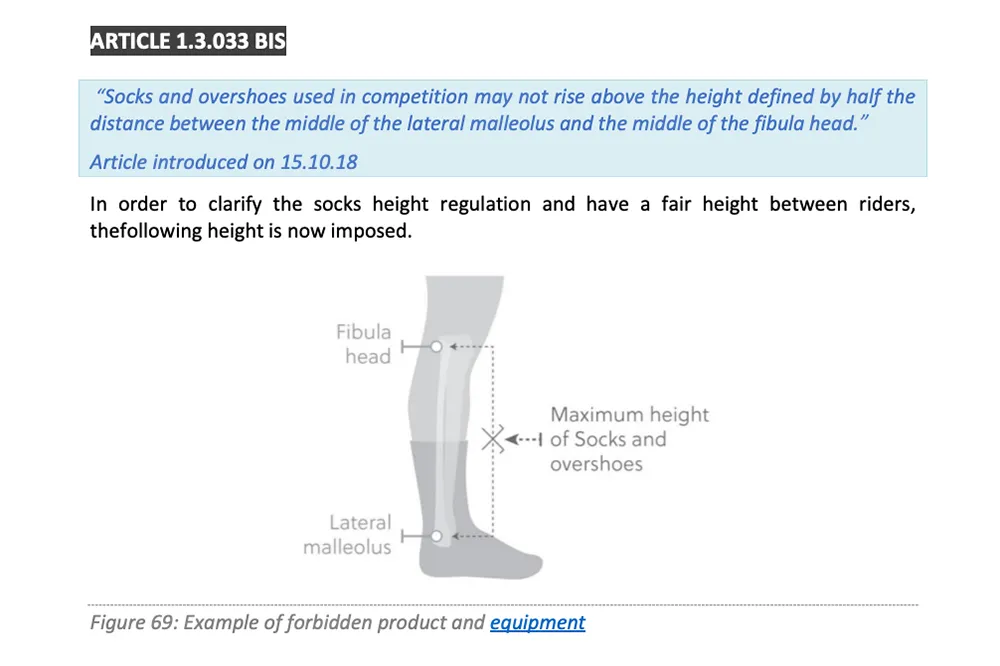

That’s not a joke: the UCI doesn’t allow your socks to extend beyond the middle of your calf because long socks can be more aero than bare legs.

In the face of far more serious issues with rider safety, this one is just a silly distraction.

So what should the UCI be concerning itself with?

Many of the longer-standing UCI regulations aim to “assert the primacy of man over machine”, while the newer crop of rules intends to improve rider safety.

Those are admirable aims, but as we’ve seen, many of these rules have an unintended – and almost always preventable – impact on riders.

The overall impression is that the UCI is tinkering around the edges, without addressing the core issues impacting rider safety.

Mandating better safety equipment and enforcing its own rules regarding course design is where the UCI should start – leave the sock heights for another day.